Chronology

The Chronology section of our website will be periodically updated with new sections to provide a comprehensive overview of Mehmet Güleryüz’s life and work. Stay tuned for these updates as we continue to enrich our resources.

Part I

Formation and Development (1958 - 1970)

The life and artistic career of the artist is divided and analyzed into key phases, starting with his educational foundation from 1958 to his departure for Paris in 1970. This period encompasses his initial enrolment at the Academy, his decision to pursue acting professionally, his return to continue his studies at the Academy, his graduation, and his military service.

1958-1962

Academy

In 1958, Güleryüz was admitted to the Painting Department of the Istanbul State Academy of Fine Arts (IDGSA). He enrolled in the studio of Neşet Günal, who had recently returned from Europe and began teaching the preparatory drawing class. In his second year, Güleryüz transferred to the studio of Cemal Tollu.

The work I did before entering the Academy was already different from the other students' work. The first year didn’t contribute much or advance my thoughts on drawing; the days passed by grudgingly responding to what was expected from us. I didn’t see much development in myself, and my initial excitement faded. I was feeding my enthusiasm more with theater, and during theater rehearsals, I began to realize that I hadn’t thought enough about art.

Güleryüz’s student years coincide with the politically and culturally dynamic period of the 1961 Constitution, which emphasized individual and social rights. However, his relationship with the Academy is described by Nan Freeman as one of discontent. Güleryüz rejected the traditional academic approach to painting, particularly the style promoted by his mentors, which was based on Cézanne’s figurative method combined with cubist elements from Léger and Lhote. Instead, he was drawn to abstraction and, by 1964, started exploring the work of New York Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, as well as geometric abstraction from artists like Joseph Albers. Güleryüz and his peers in Istanbul were unaware of the emerging figurative art movement of the late 1950s and early 1960s, particularly the works of artists like David Hockney and Jasper Johns. This lack of exposure led Güleryüz and his contemporaries to find their own path toward a new figurative style.

1958-1962 Period Works

1963

Theatre

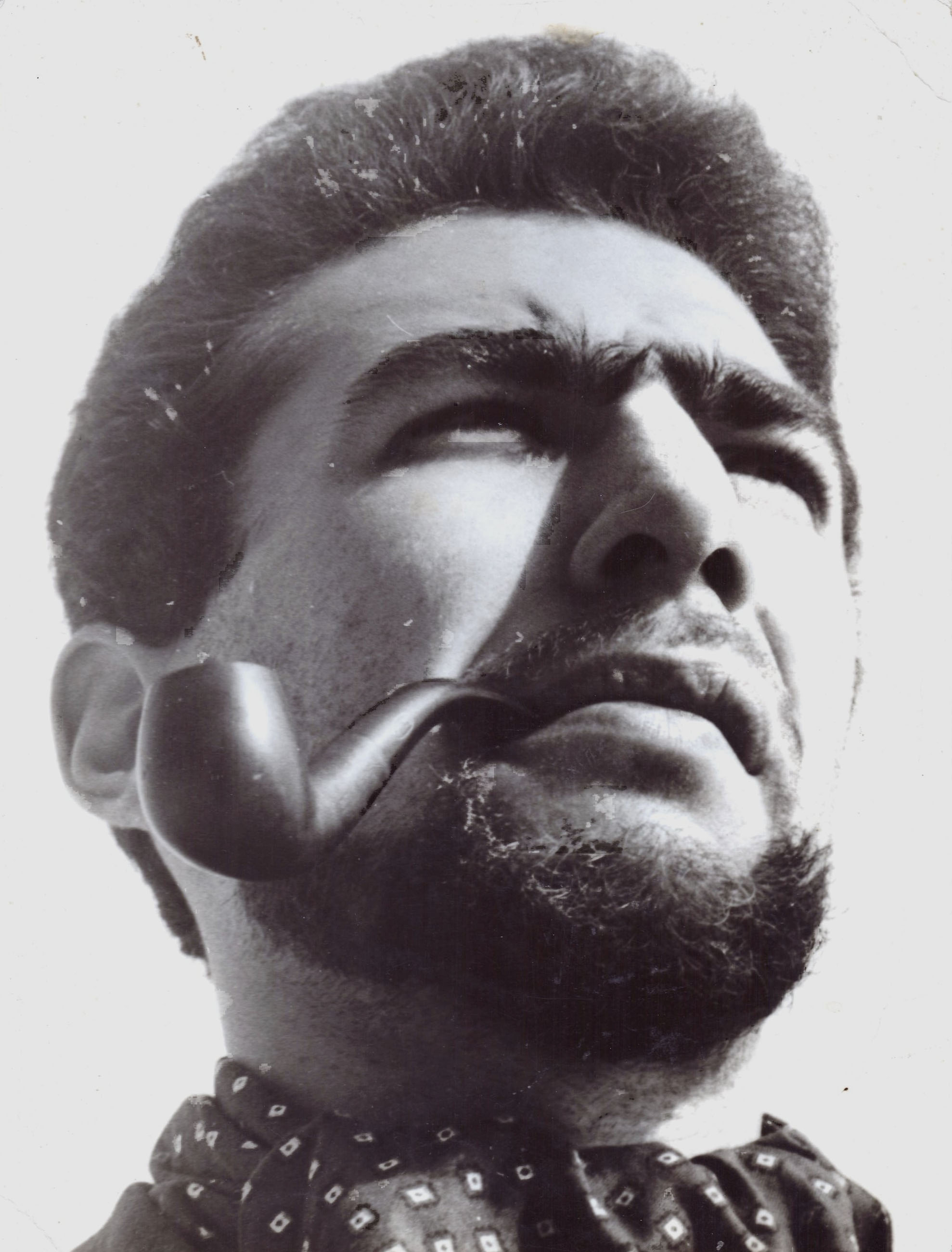

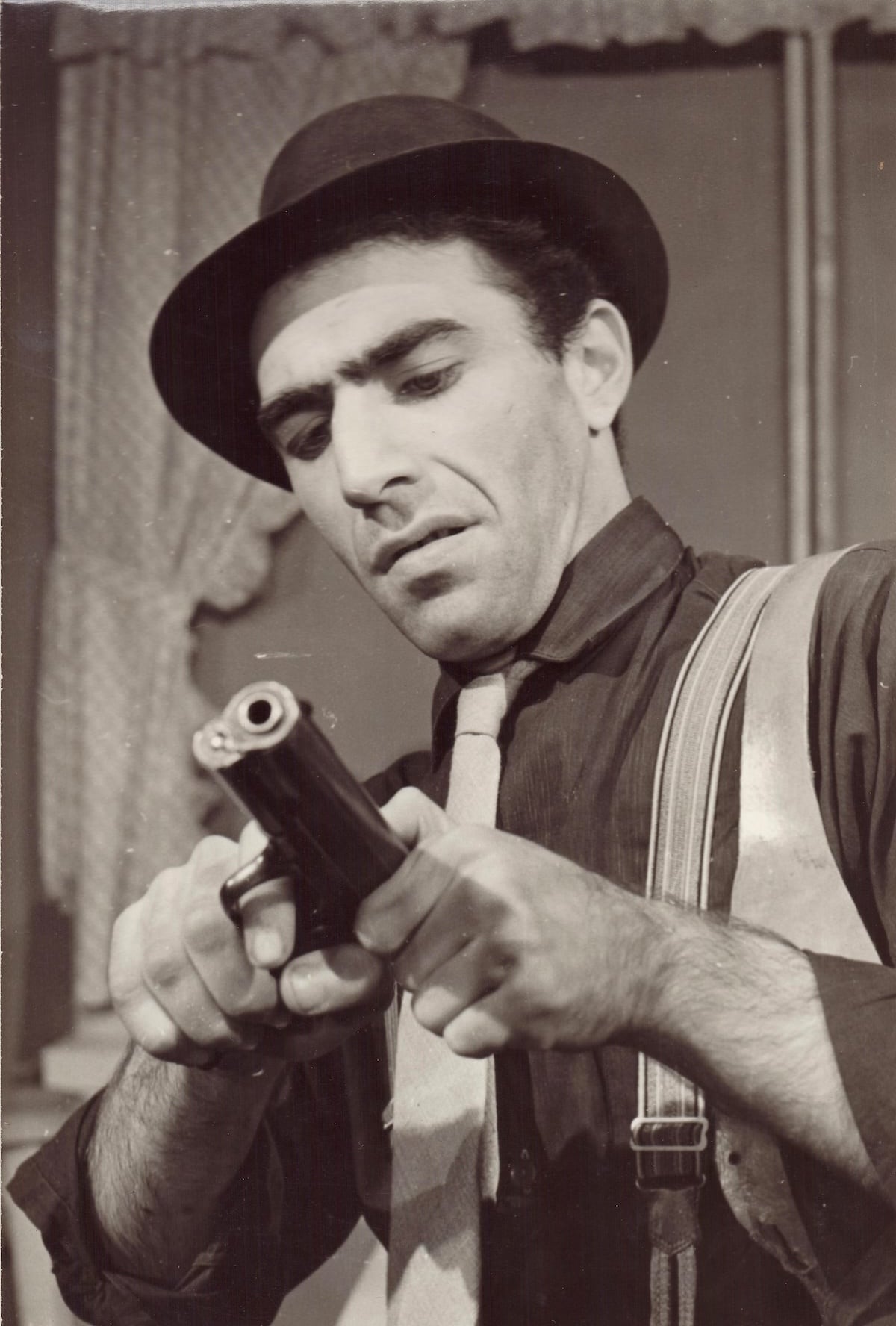

Despite his increasing interest in the visual arts, Güleryüz sustained his passion for theatre. During his years at the academy, he joined the Academy Theatre. Subsequently, he participated in “actor studios” and acting courses at The Cep Theatre under the mentorship of distinguished instructors such as Haldun Dormen and Beklan Algan, refining his acting abilities in significant theatrical institutions. His engagement with theatre profoundly shaped his subsequent artistic development, particularly in terms of how the human form, gestures, and behavioral expressions would later manifest in his paintings.

I learned the intellectual foundations and reasons behind the creation of art during those studies. Prior to working on texts, we learned the structure through the objects we chose. We conducted a series of studies on how we could gather thoughts in a particular object. Preparing your emotions and body for acting training, hearing beyond, in other words, preparing the inner space, rehearsals...

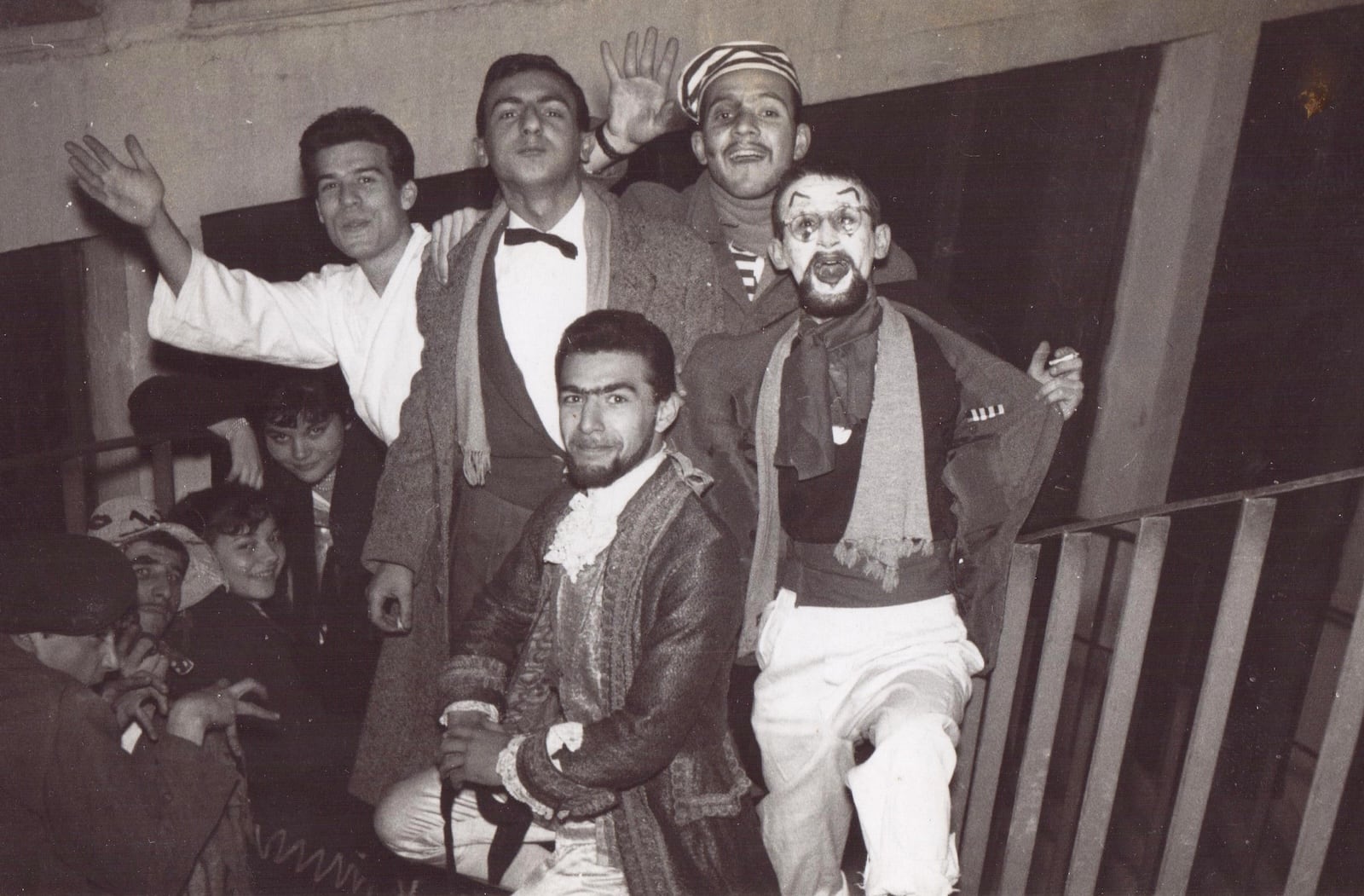

In 1963, Güleryüz made a pivotal decision to leave the confines of traditional academic training, dissatisfied with the limitations it placed on his creative exploration. Seeking more freedom, he aligned himself with the progressive Arena Theatre Group, a collective that was at the forefront of avant-garde theatre in Turkey, led by Asaf Çiğiltepe. Güleryüz, who performed in the group's inaugural play "Übü," also participated in all subsequent productions by Arena while simultaneously designing the costumes for these plays. Immersed in an environment that encouraged experimentation and innovation, Güleryüz explored new avenues for self-expression. The insights and techniques he cultivated during this period would later become integral to his transition into visual art, where his work would reflect the same boundary-pushing spirit he found within the theater.

During this phase of prioritizing theater, Güleryüz discovered an opportunity to channel forms of expression that he could not fully realize through painting as he had envisioned, by engaging directly with audiences onstage. This period also enabled him to connect more intimately with the pressing issues of his time. The character archetypes—shaped by the forms, gestures, and behaviors manifested through the human body in theatrical performance—along with the solutions crafted through the stage décor in which these characters were situated and their interaction with the performance space, profoundly influenced the paintings he would later produce. These elements collectively found expression in his subsequent visual artworks.

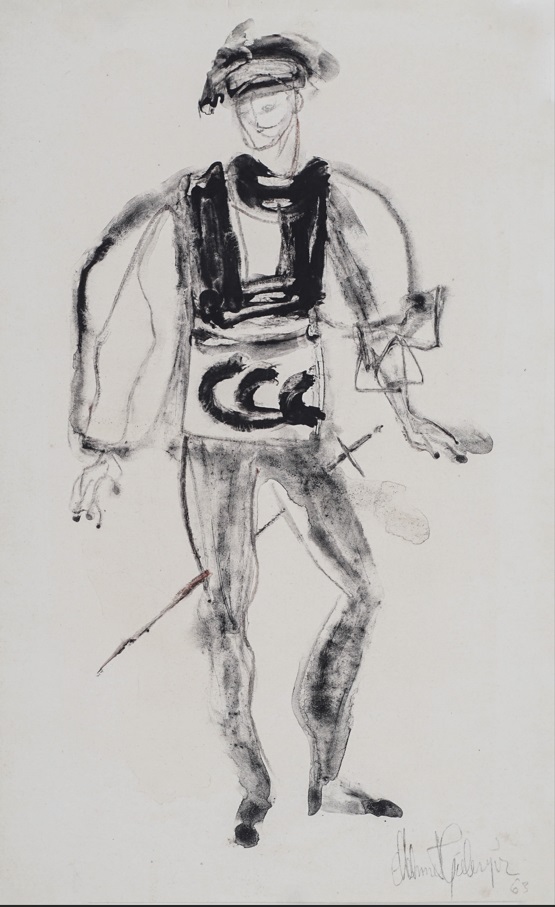

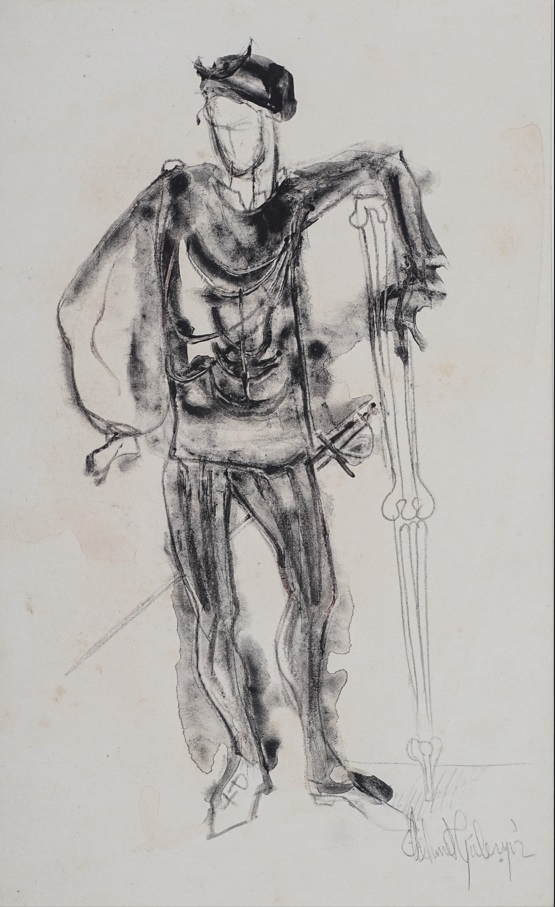

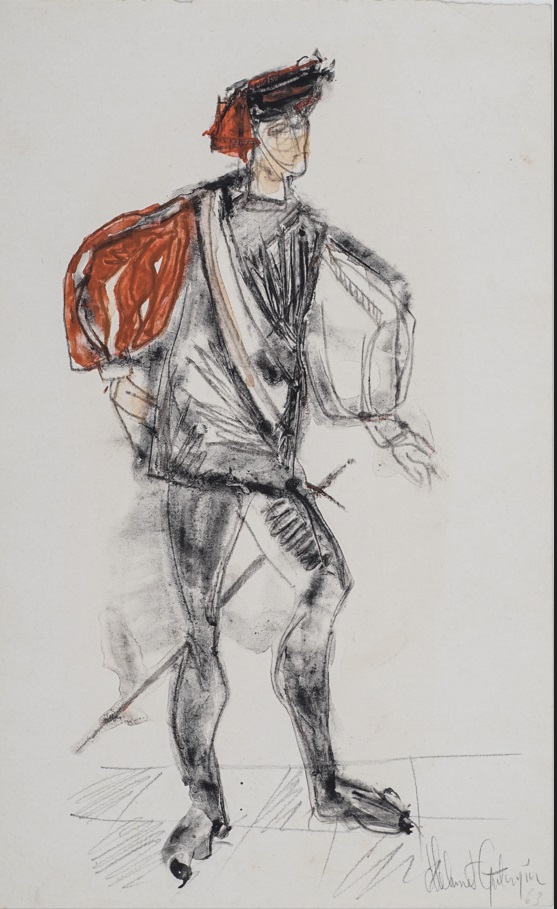

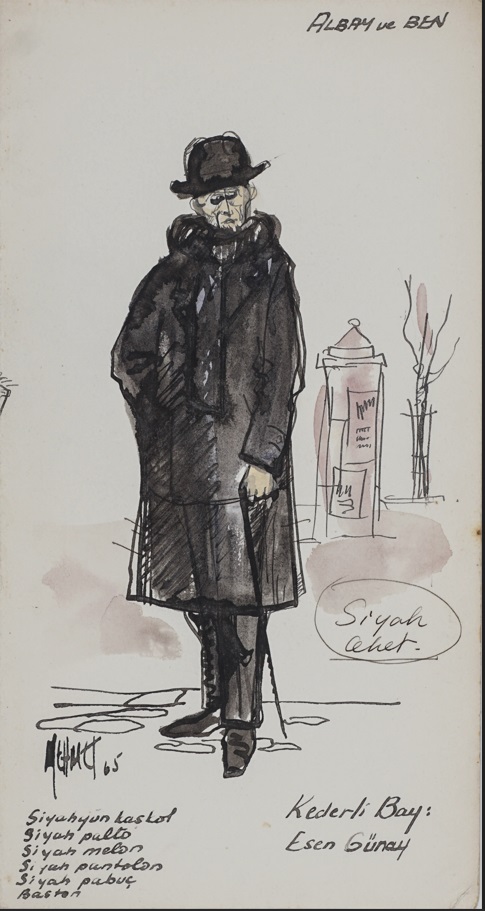

Costume Designs

1963

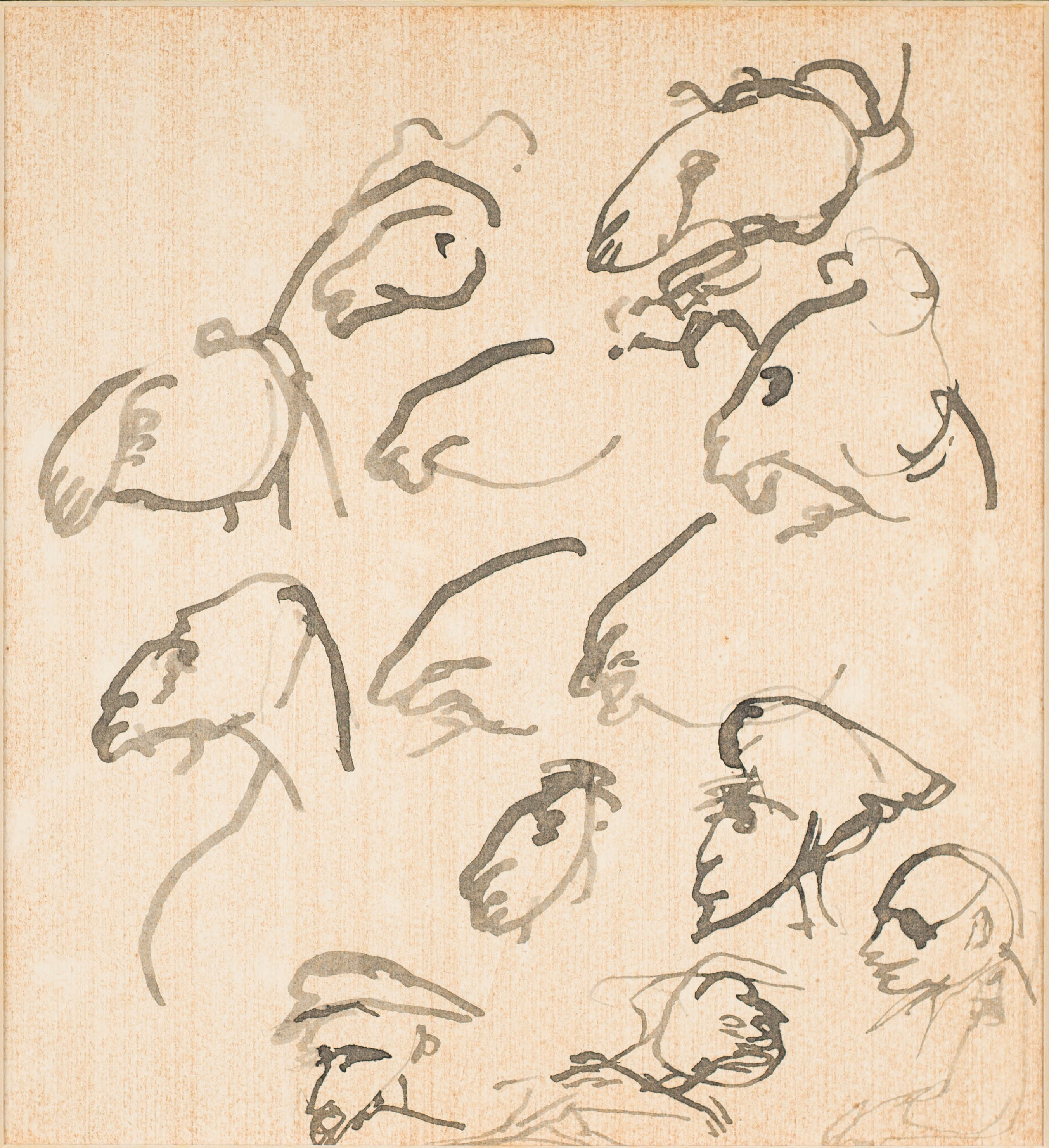

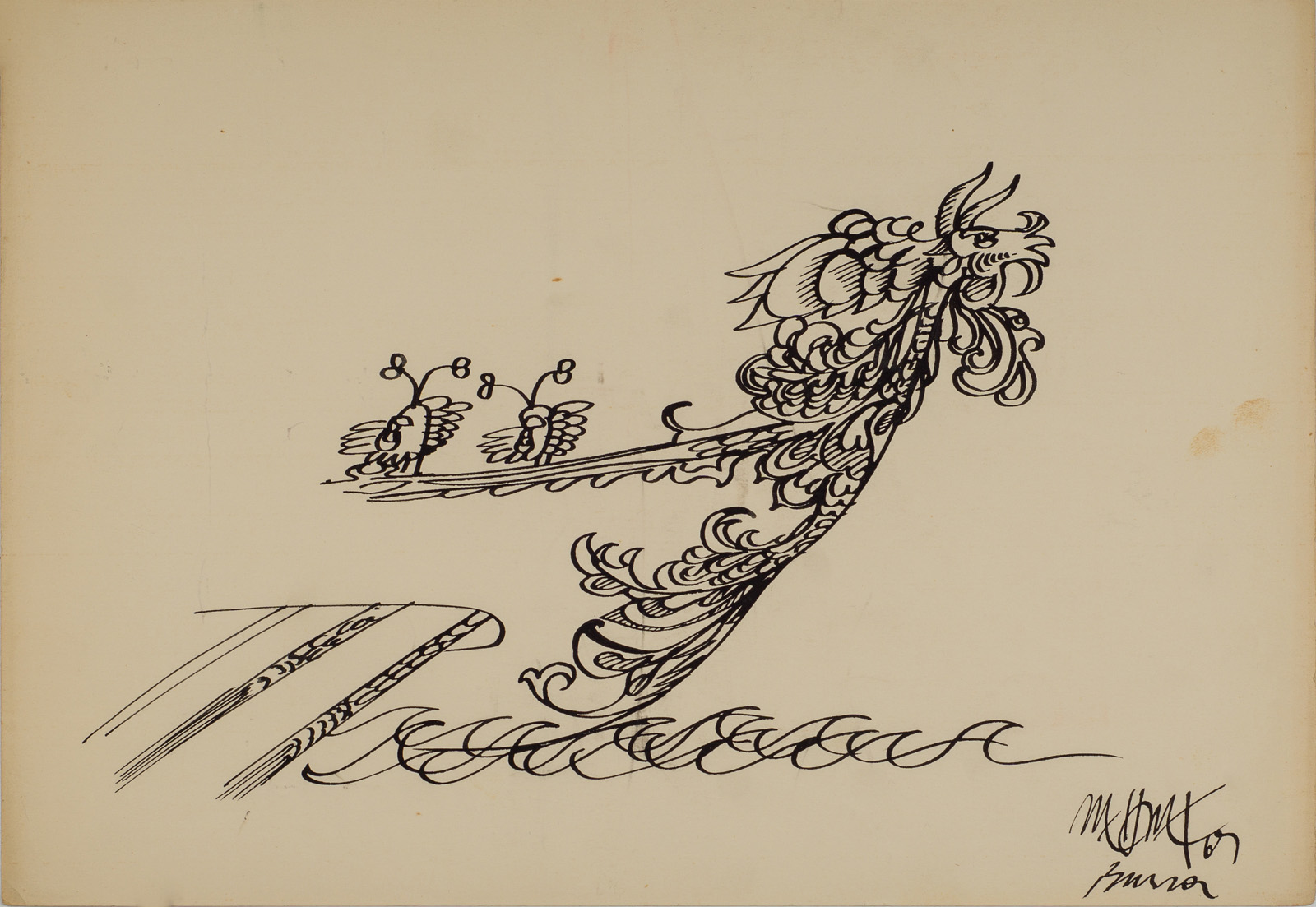

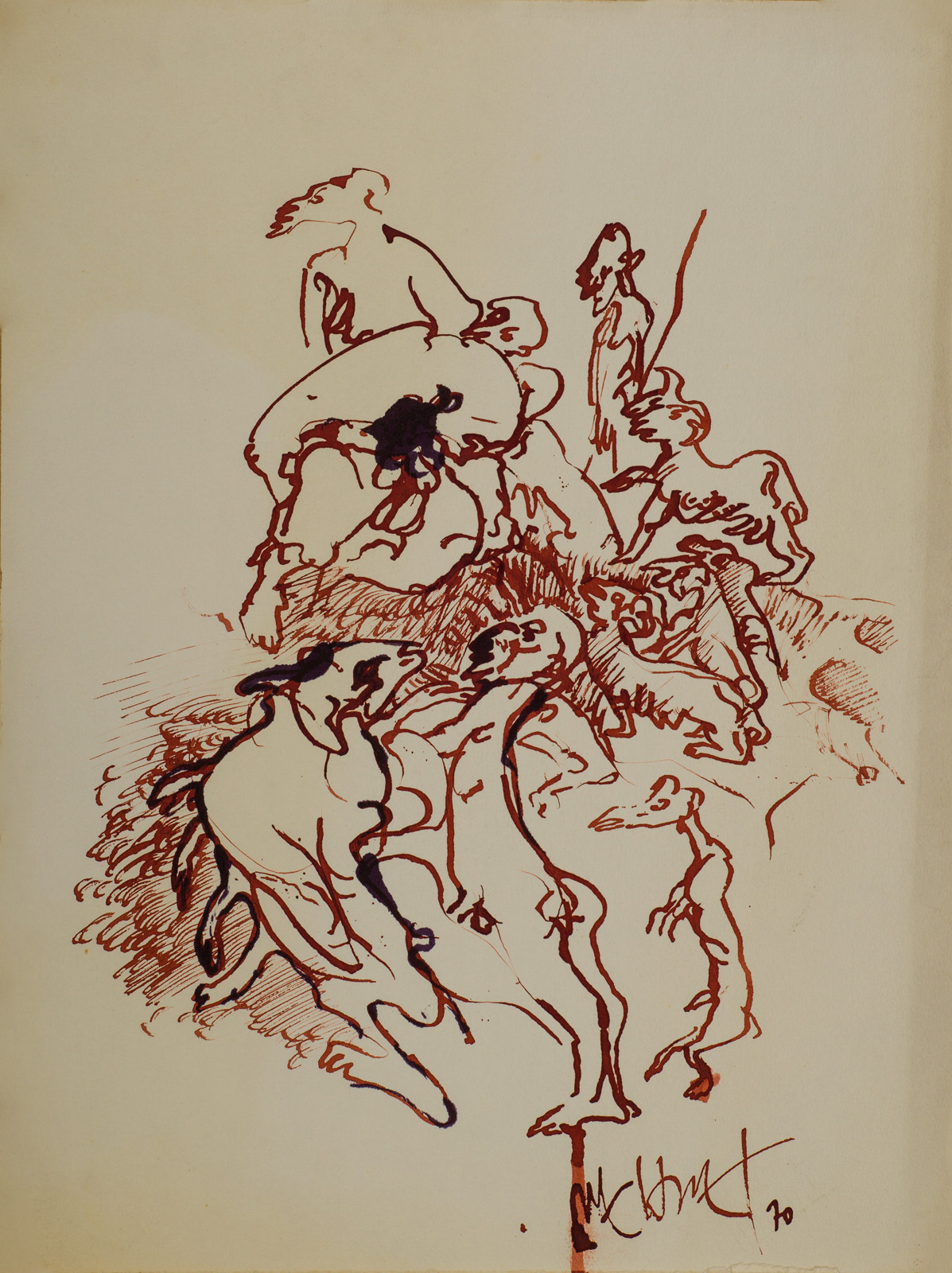

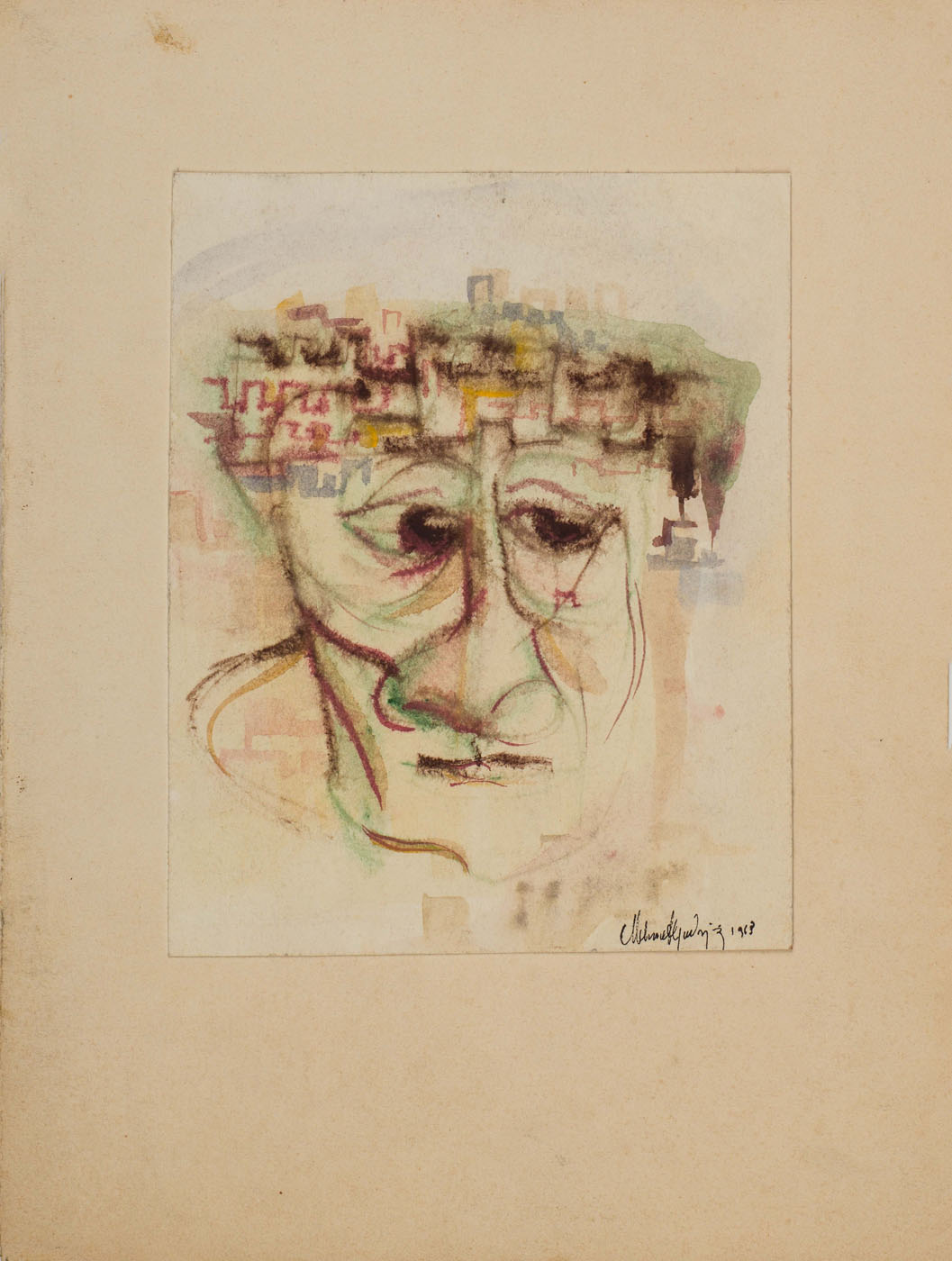

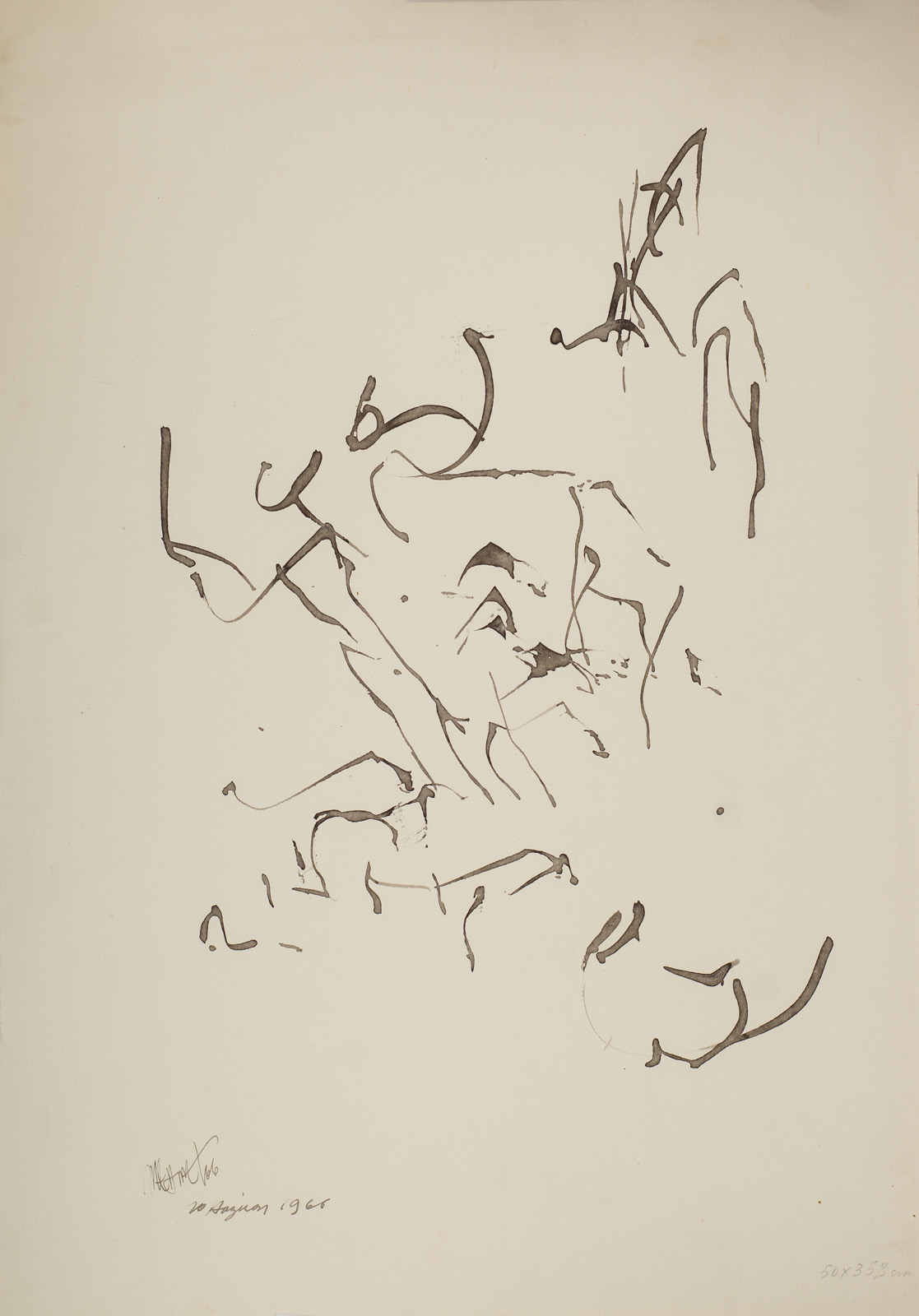

City Gallery: Sepia drawings

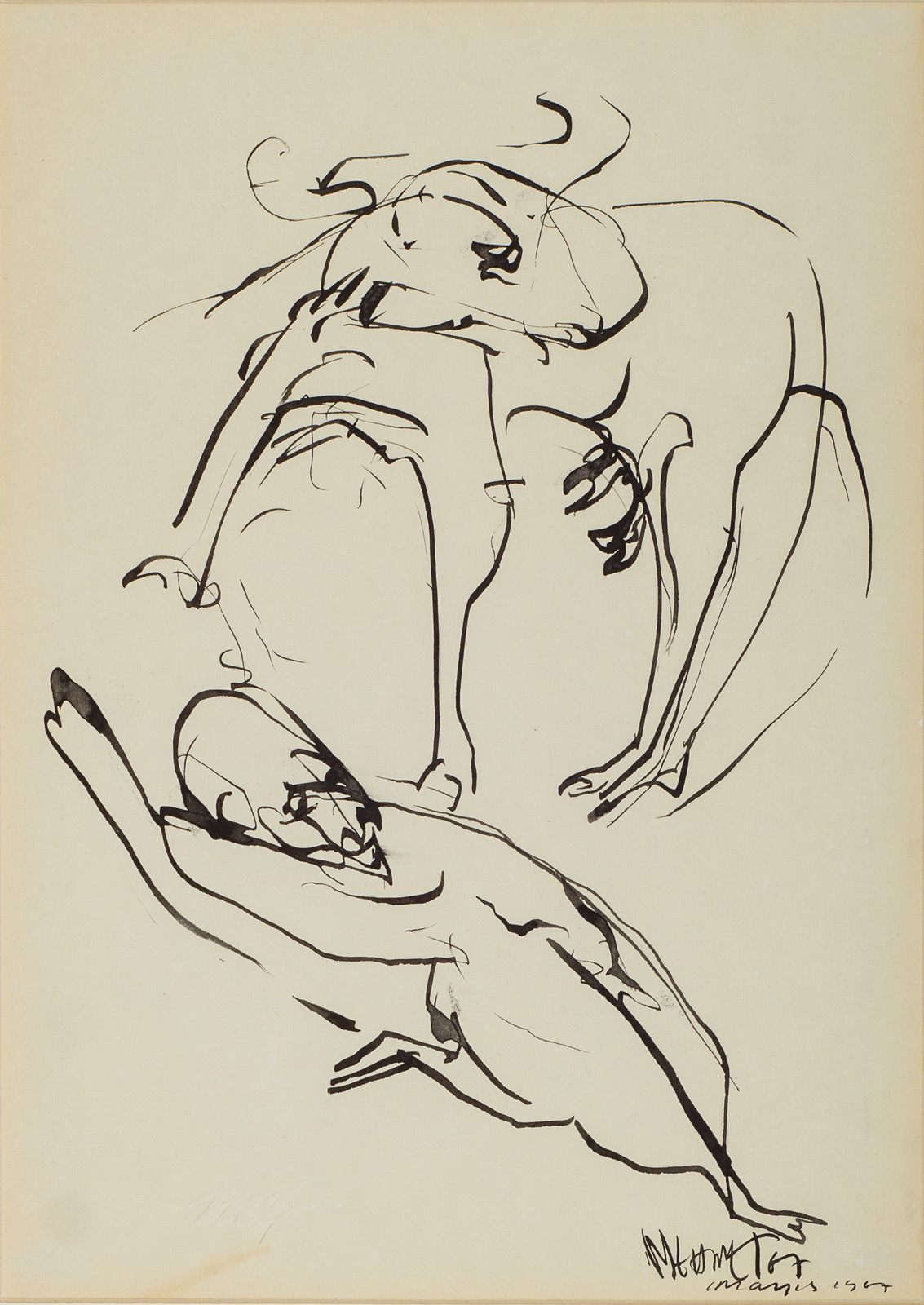

At the beginning of the summer of 1963, right after returning from a tour, Gülerüz creates a series of sepia drawings. For the first time, he experiments with a new medium: drawing directly on wet paper with watercolor tubes. The way the colors spread in this technique resembles Chinese ink wash painting. These works focus on nudes and interiors, exploring the concept of space as seen in Far Eastern art. Using the same method, he also experiments with rhythm based on speed in black and white drawings.

Back then, it was not well-received by the professors. There were very few people looking at art, and there were no buyers. The most important thing about having an exhibition was to be able to see and show your paintings together. I still have a significant number of those works; when I look at them today, I see that they are sincere attempts with some solid qualities, and they contain signs of the path I followed. Most importantly, they were created by a hand that understood what was needed.

Canan Beykal, has this to say about the works of Güleryüz during this period, ” ...a talented hand that has not yet deviated from the path is at work in these drawings. It employs in masterly fashion the norms of rhythm, form, light, and shadow which the Academy, with its principle of the aesthetically attractive, harmonious, beautiful, and balanced composition, would exact of its students, is at work in these drawings. (...) But Mehmet Güleryüz’s drawings, above all because he can draw with an astounding leisurely pleasure, should have come into being spontaneously despite himself, as in the case of the masterly author playing with words. (...) But if the viewer is careful to consider the characteristics of the conventional studio drawings, the freedom of the 1963 drawings will not fail to strike the eye. One may even ask, with regret, why Mehmet Güleryüz eventually abandoned this type of drawing, which helped him produce works that are likely to please and interest quite a few viewers.

1963: City Gallery - Sepia Drawings

1963-1965

Return to the Academy

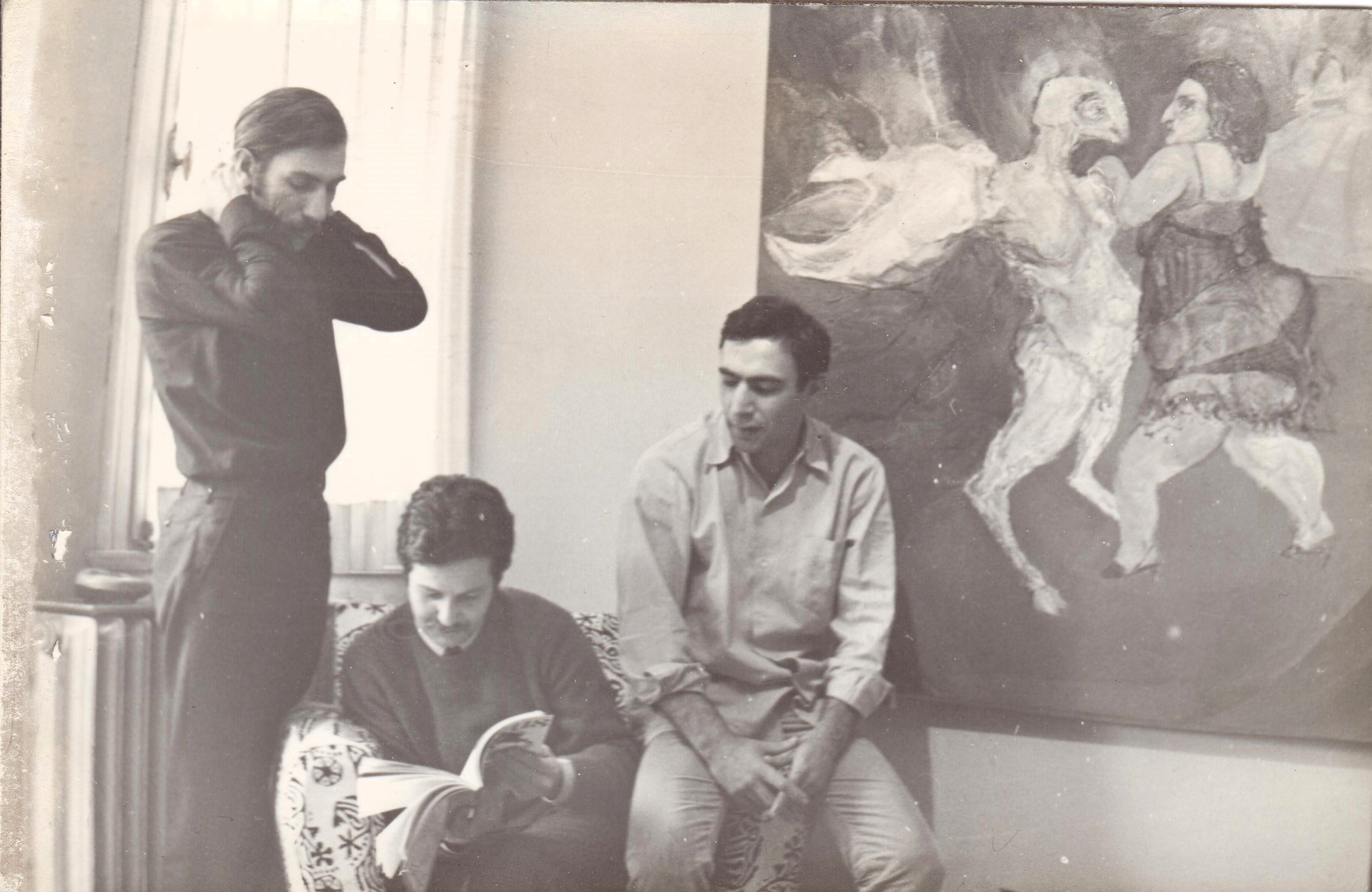

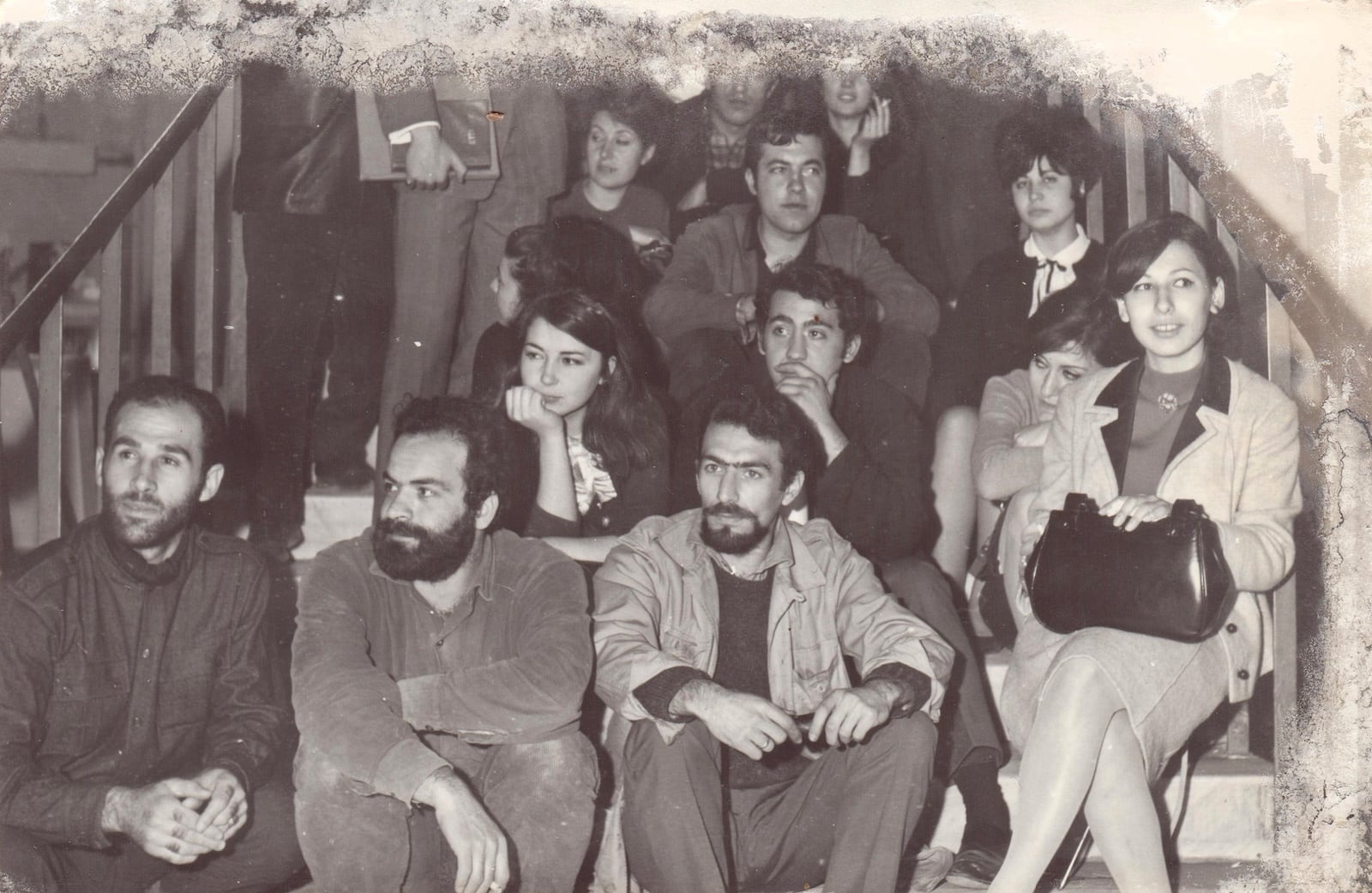

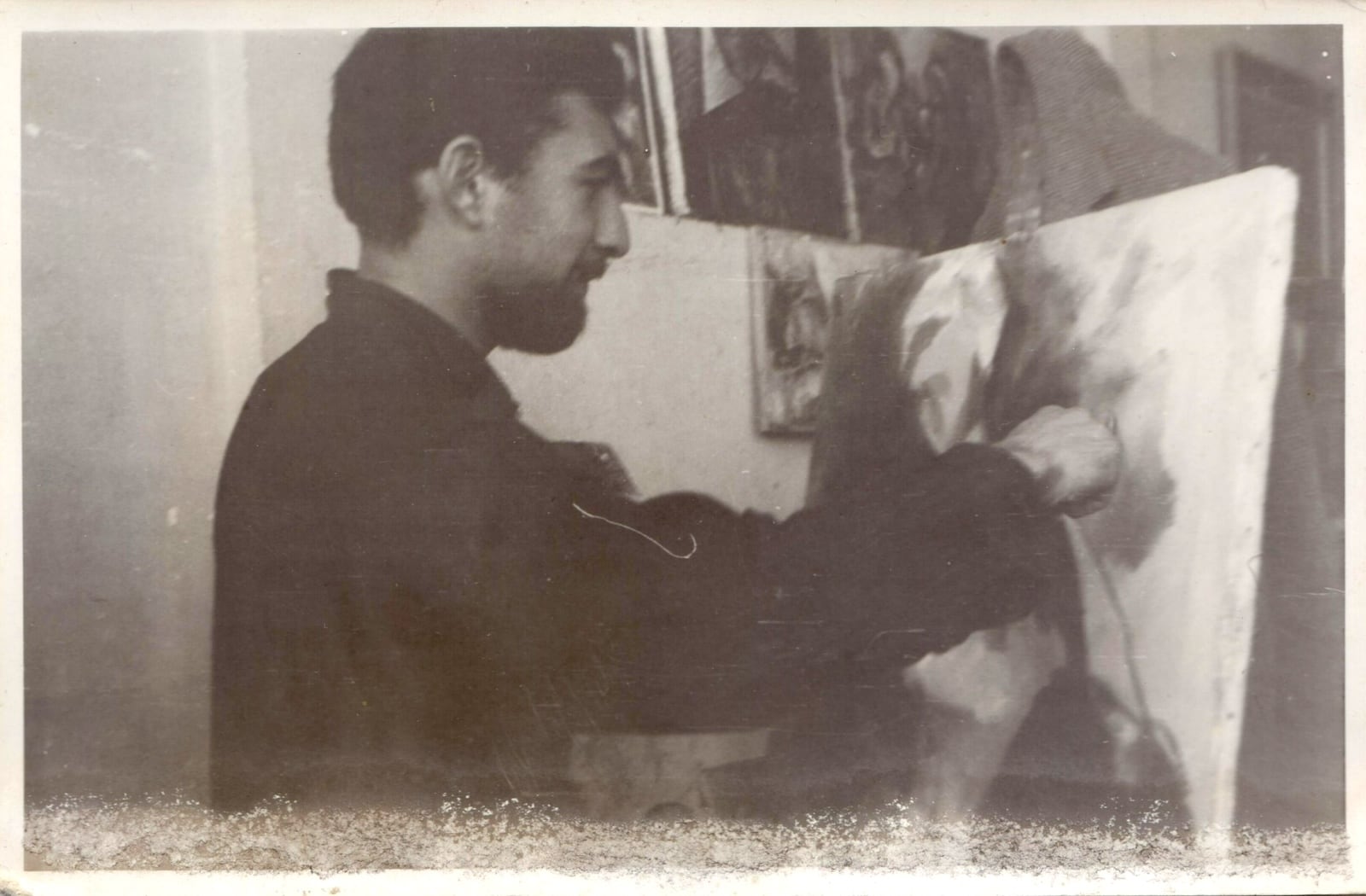

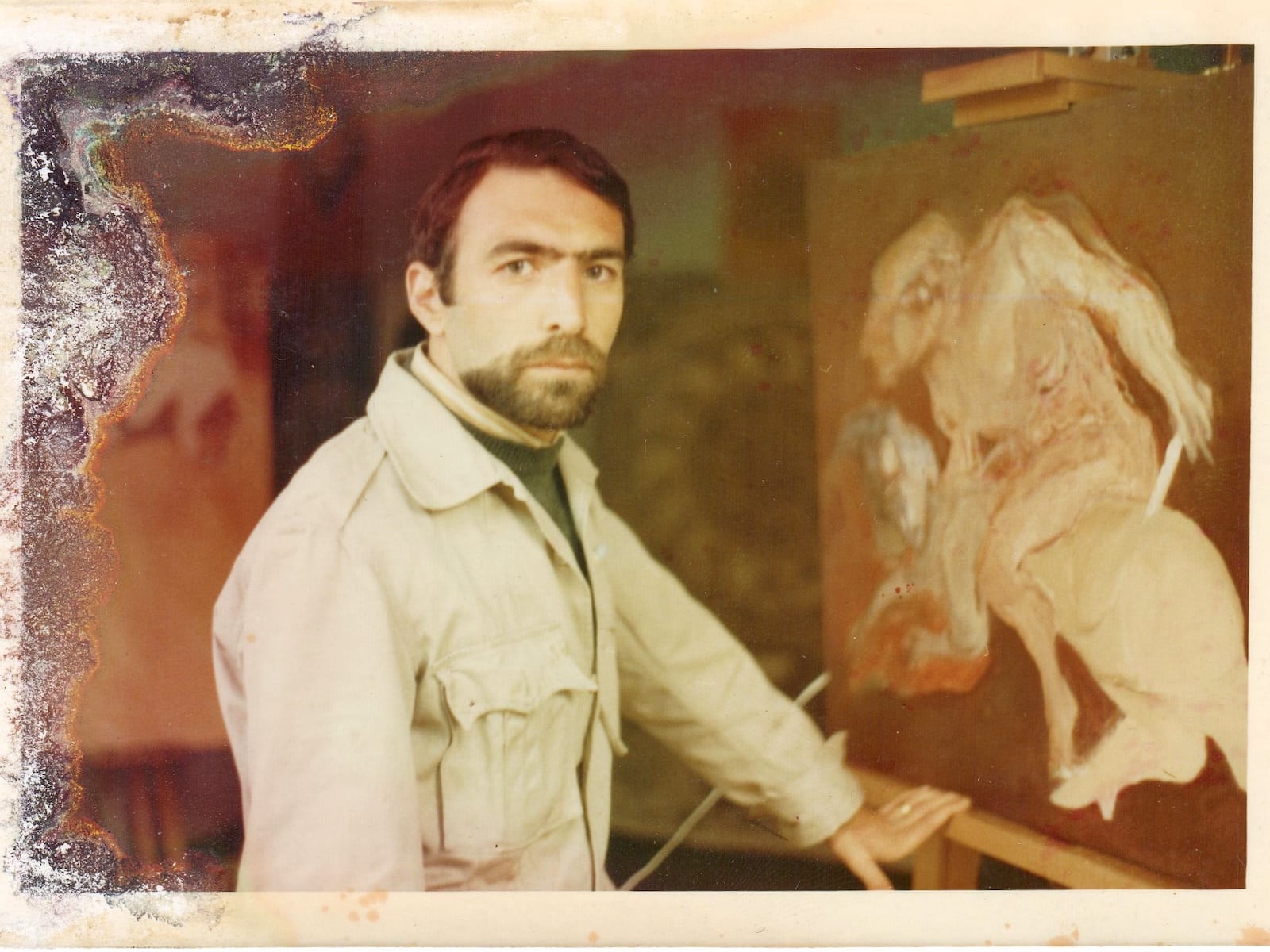

Mehmet Güleryüz with colleagues at the Istanbul Academy of Fine Arts, 1965. © Estate of Mehmet Güleryüz.

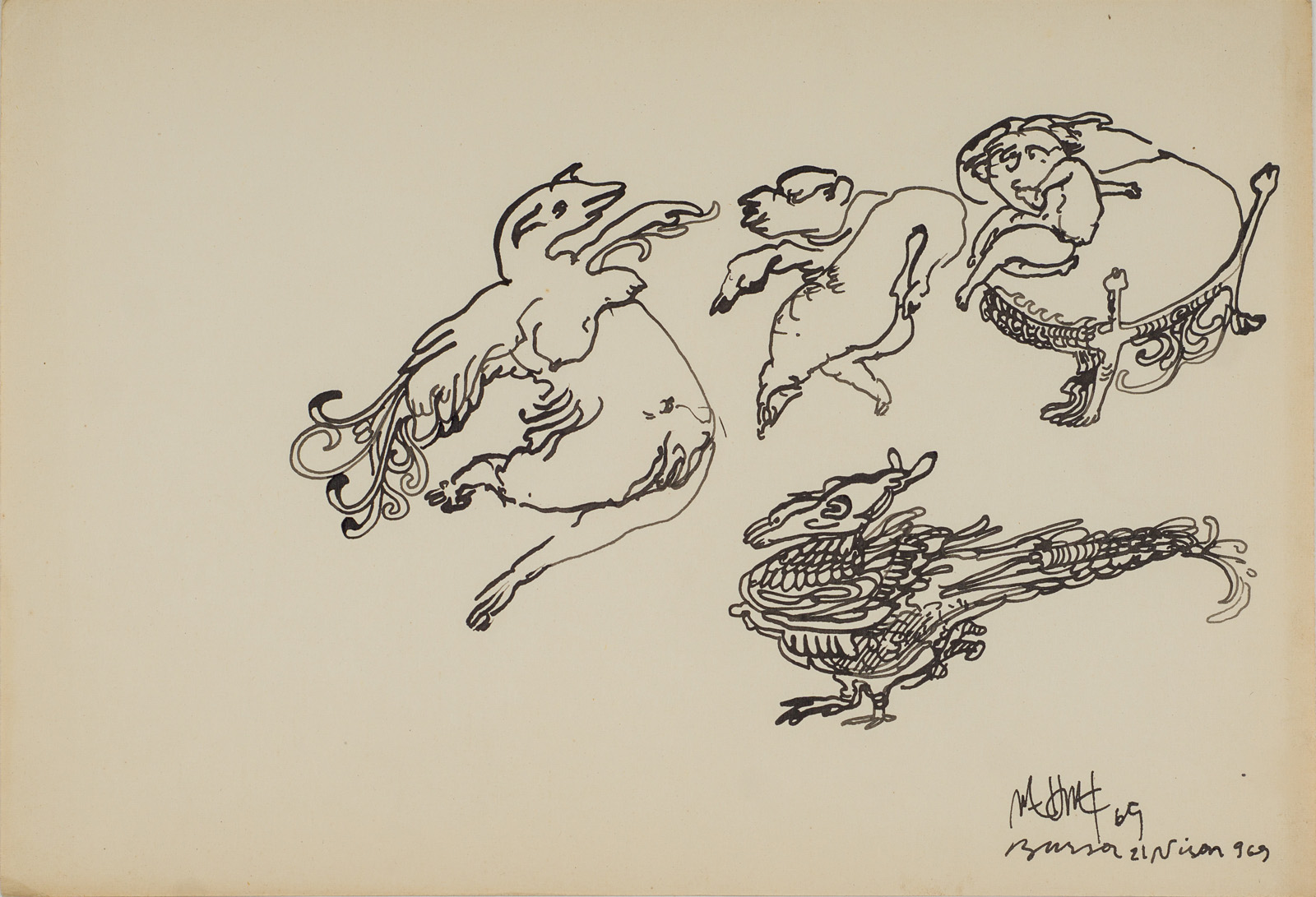

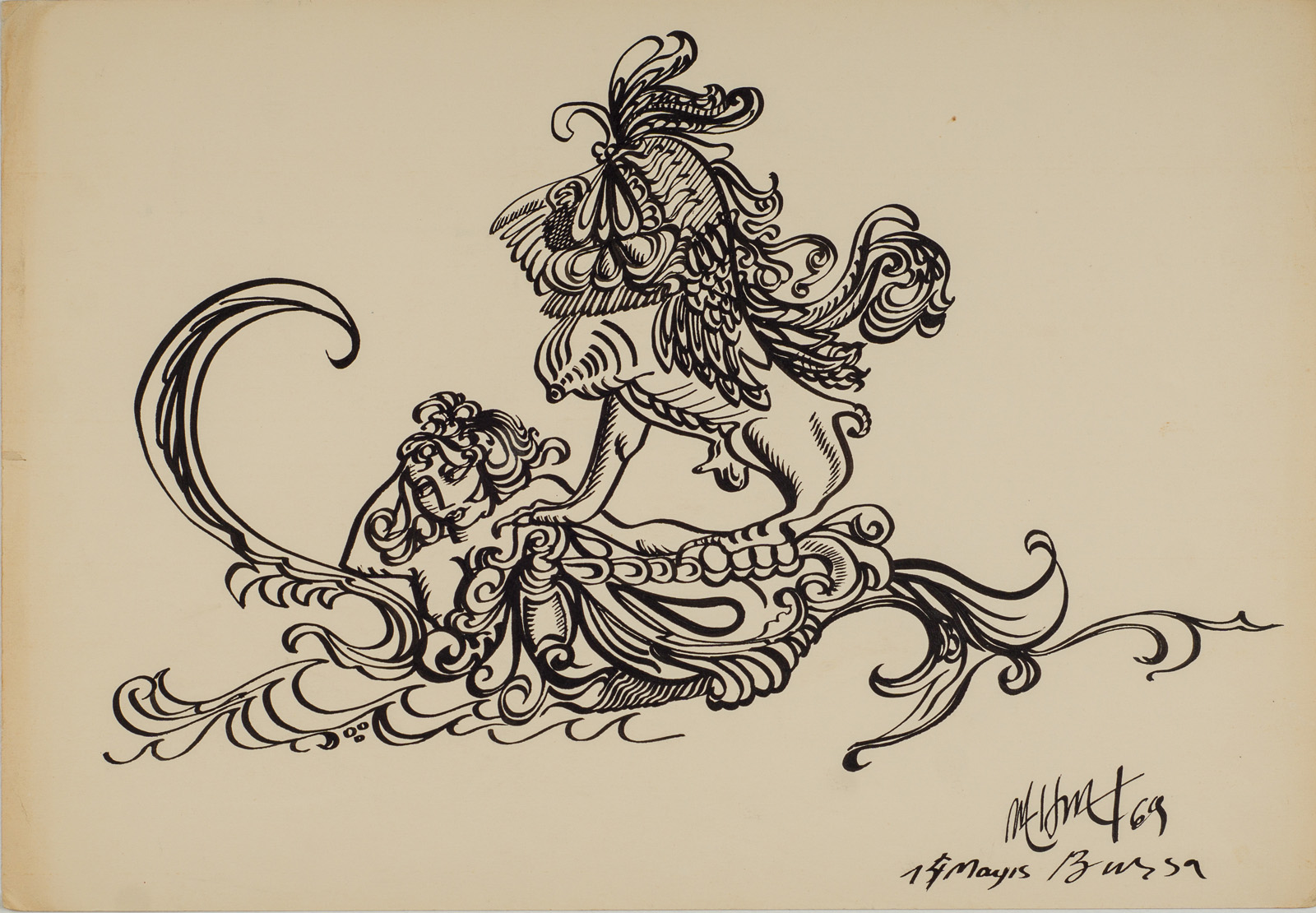

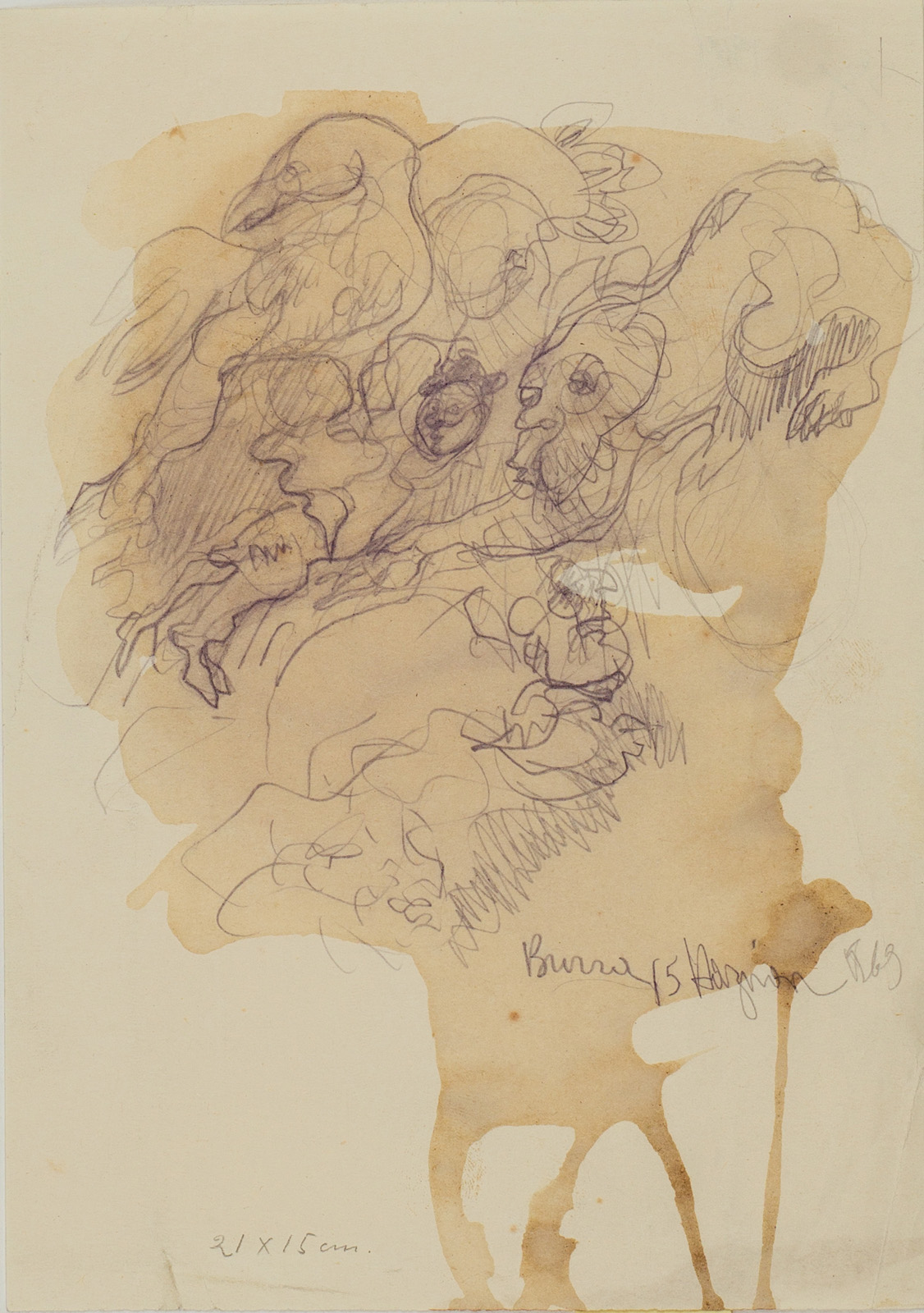

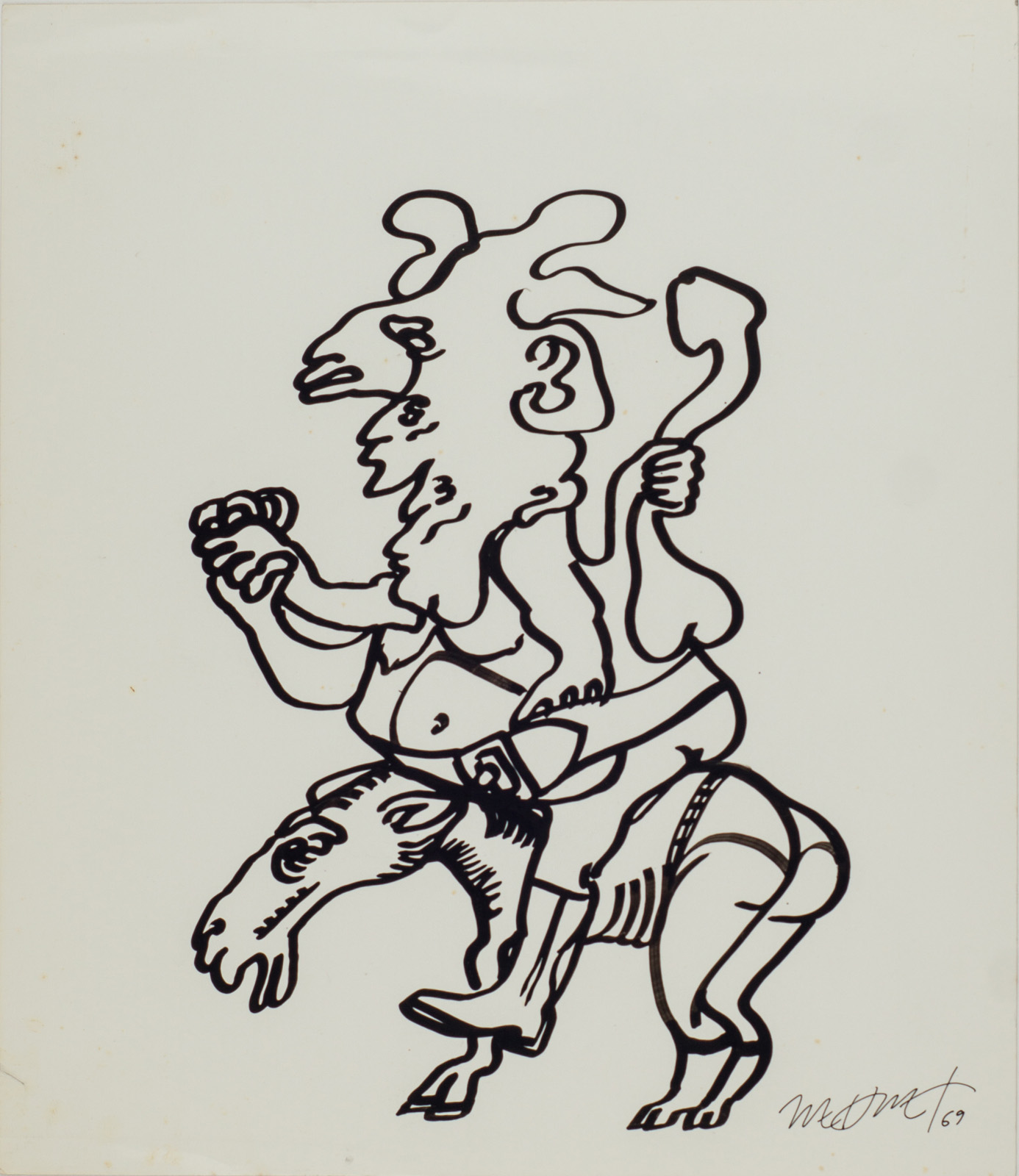

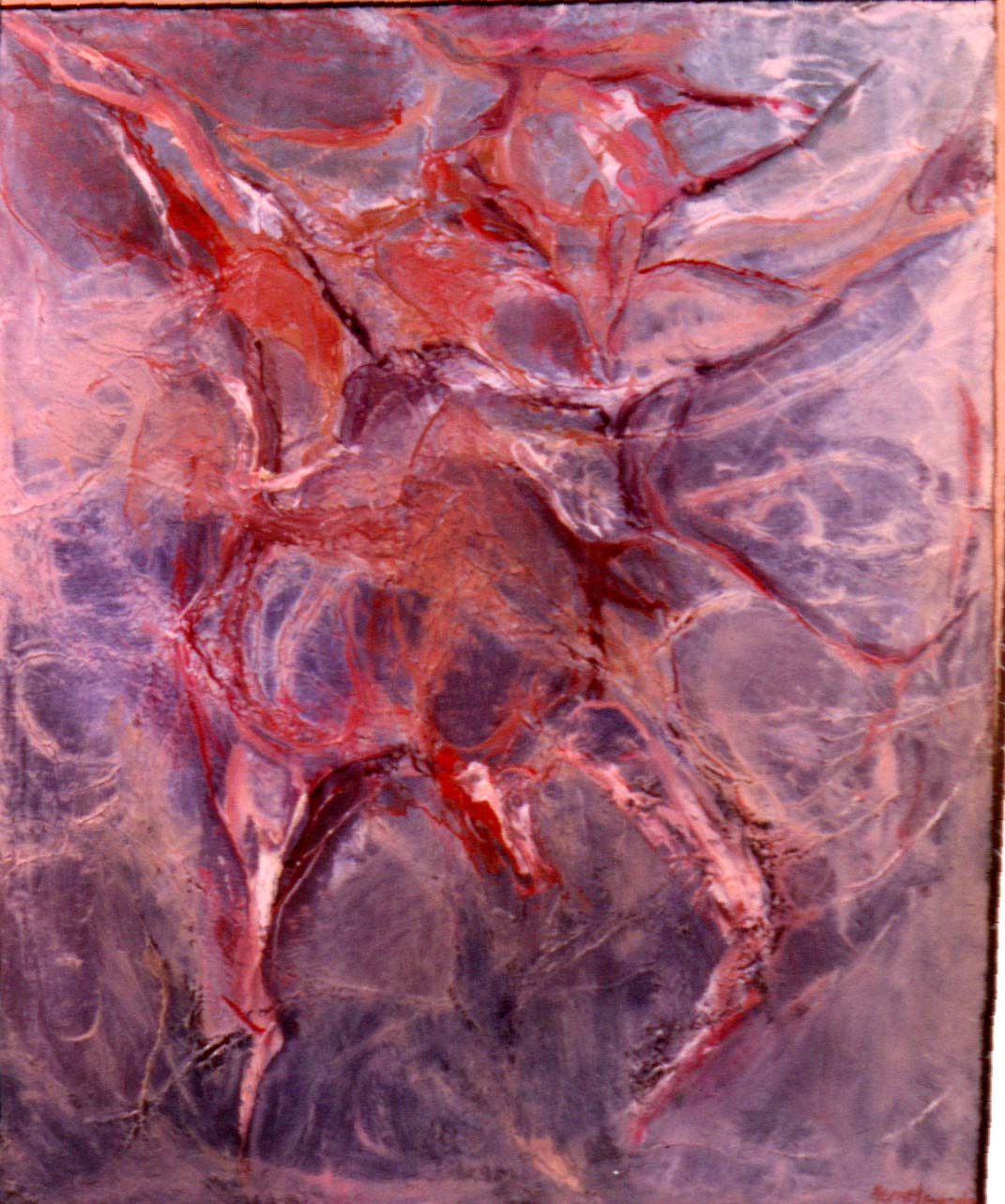

In 1963, when Mehmet Güleryüz returns to the Academy, he continues on at Cemal Tollu's studio. Since he realizes that the issues of expression in theater interest him, he turns to expressionist painting beyond abstract works. In 1963-64, Güleryüz establishes a connection with the figure and begins studying figures in dark tonalities. One of his references is trying to find the texture of Turkish embroidery motifs and Coptic weavings in painting. Using emerald greens, vermilion reds, thick paint, and a palette knife, he works on a series of paintings, creating texture with the spatula, varying the consistency of the paint through different strokes, and working with drawing-based compositions of interconnected human and animal figures. These are stylized surface paintings, but they do not reveal themselves much. At that time, Güleryüz thinks about African and cave paintings, the simplifications in primitive stylization; among his experiments, there are also nudes that do not reveal themselves in the darkness.

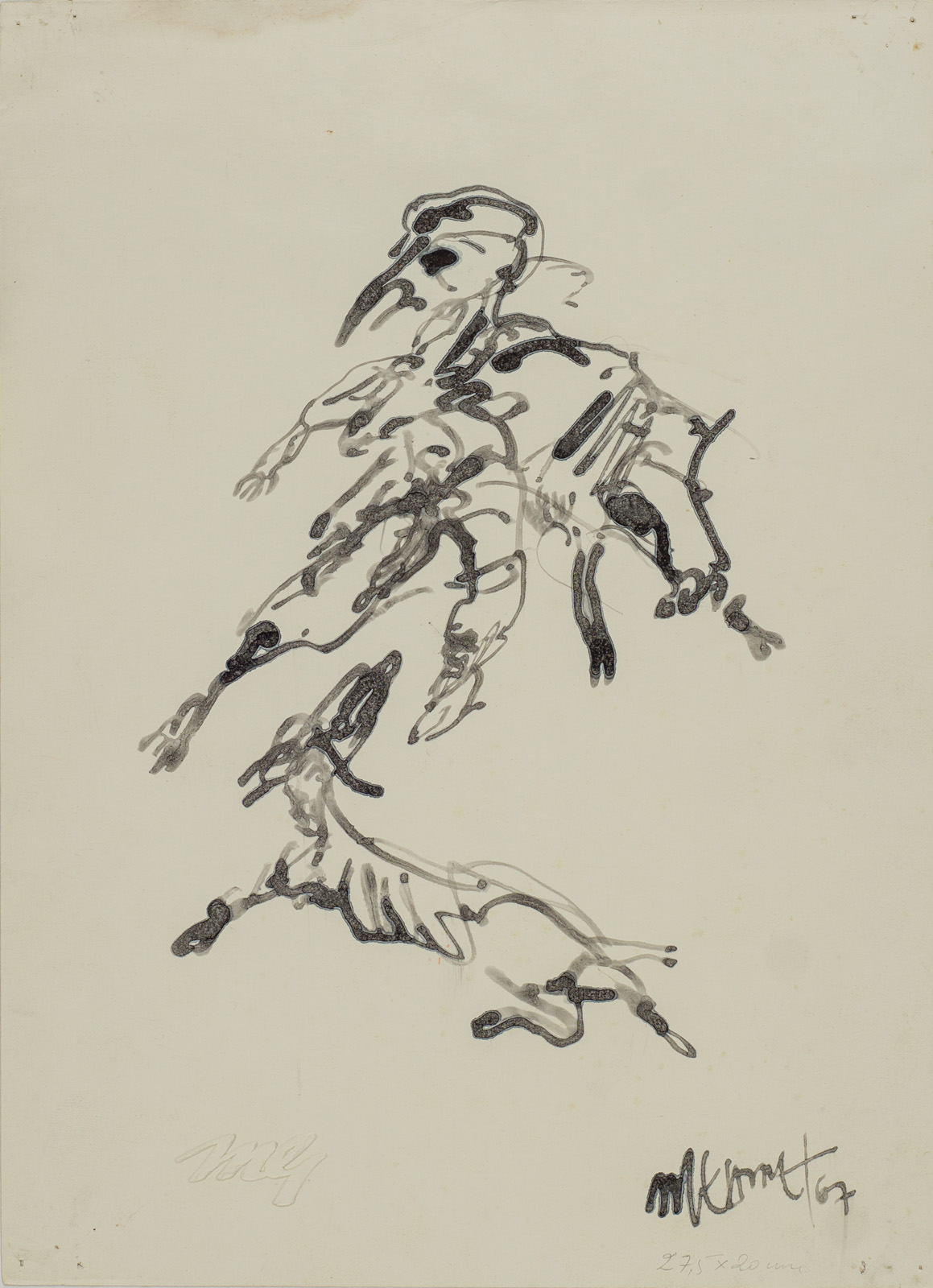

I started the 'Caucasian Chalk Circle' series of drawings at (the studio in) Galatasaray. I created animal and human motifs that carried traces of the Far East, which did not directly correspond to Brecht's text, discourse, or even the images in the play. I focused on issues in primitive, nomadic societal structures, the human form, of coexisting with animals. It is very difficult to explain why I chose these themes. The animals were not distinct; they seemed to be in a state of metamorphosis and took on fantastical roles. I wanted to create a world with a difference I found in the language of drawing, a world that I couldn't name. Later, when I thought about it, I realized that by preferring an undefined description, I had opened a dynamic space in the work; I had uncovered an unconditioned form of the emerging atmosphere." I followed the same path in creating the figure; I believe I established a language that is not strictly tied to reality, but one that can create poetry starting from it.

In 1965, he sets out with the principle of opposing Academy aesthetics, and creates the “5 Young Painters” group together with Utku Varlık, Devrim Erbil, Oktay Anılanmert and Necati Ayden; the group holds two exhibitions.

Semra Germaner interprets the development of art in Turkey of those years in the following way: "In Turkey, just as much as in the rest of the world, the year 1968 has been a time of awakening and transformation that left deep imprints in all arenas from politics to cultural life. In the period of 1960-1970, while these effects were very clear in the field of literature, the field of plastic arts witnessed the apparent pursuit of figurative expression as an alternative to active abstract art, by young artists like Mehmet Güleryüz (1938 Istanbul), Alaettin Aksoy (1942 Trabzon), Komet (Gürkan Coşkun) (1941 Çorum), Utku Varlık (1942 Bolu) and, albeit displaying a different artistic identity, Neş’e Erdok (1940 Istanbul). One understands that these artists wanted to reflect in their works a particular attitude toward life, their own inner worlds and social commentary."

The same year, he meets the American Carol La Motte, who has come to Istanbul with the Peace Corps Program. While Carol is working at the dormitory of the Society for the Protection of Children (Çocuk Esirgeme Kurumu) in Kocamustafapaşa, they begin a relationship shortly before she is due to return to her home country.

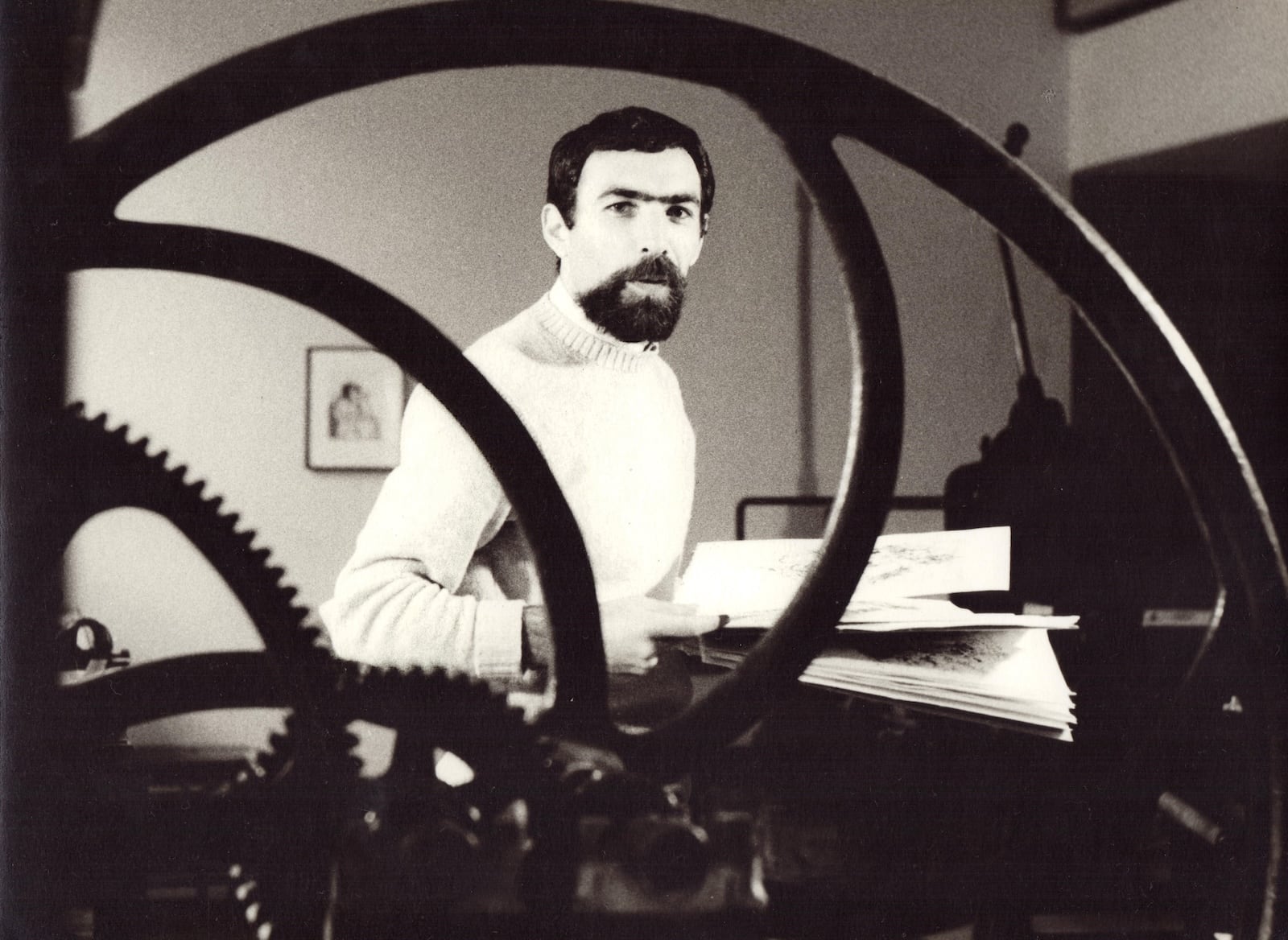

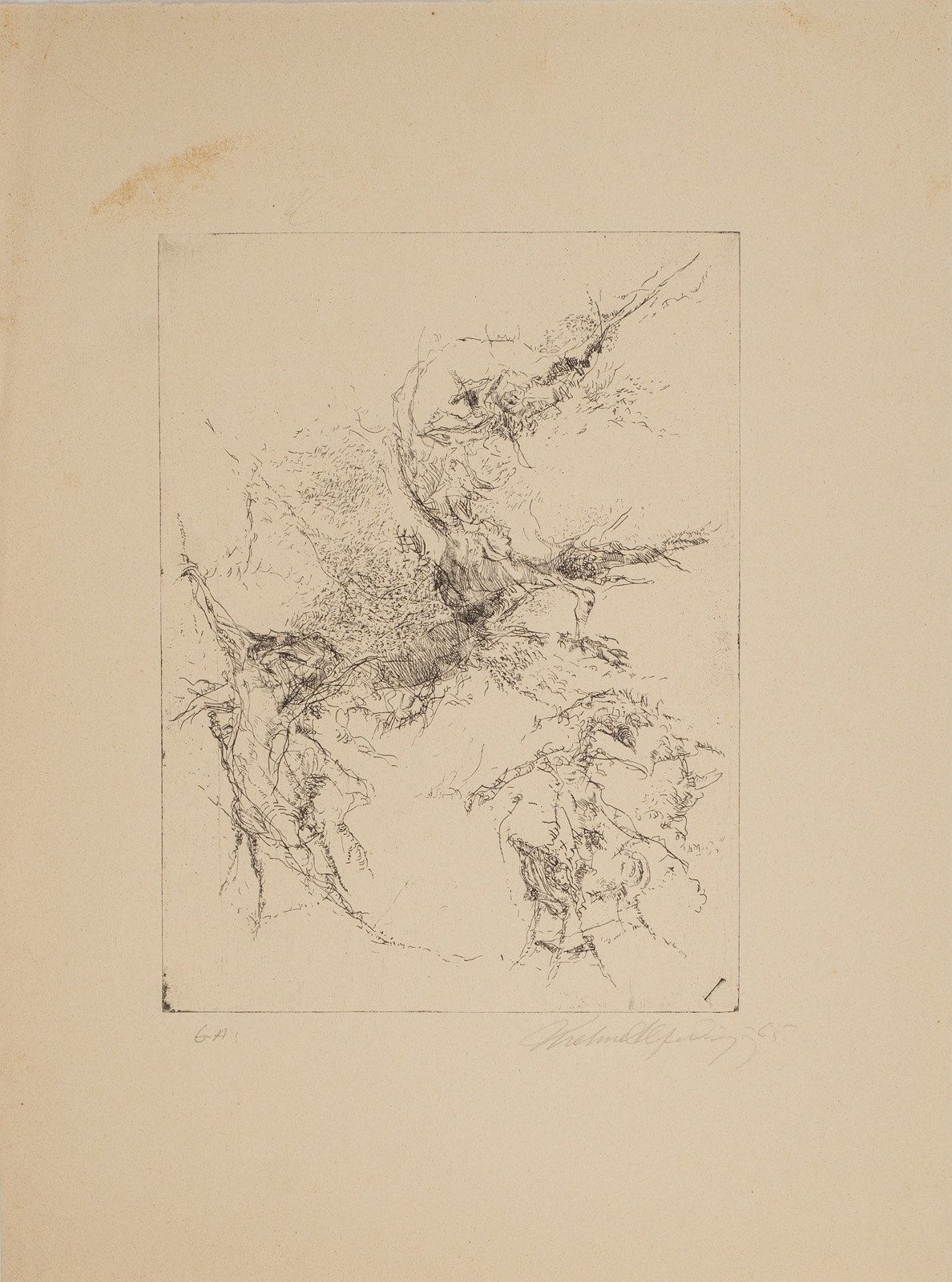

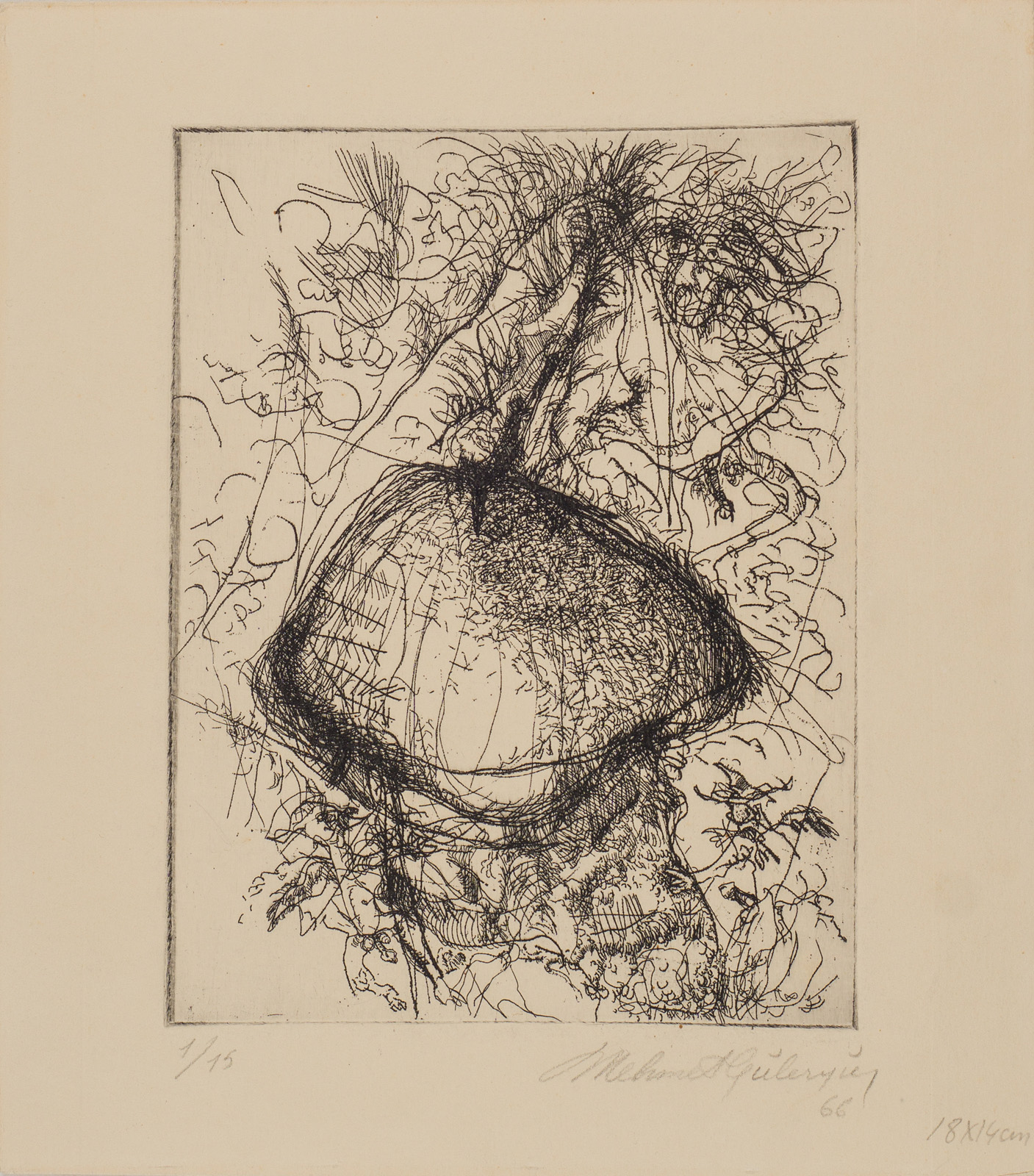

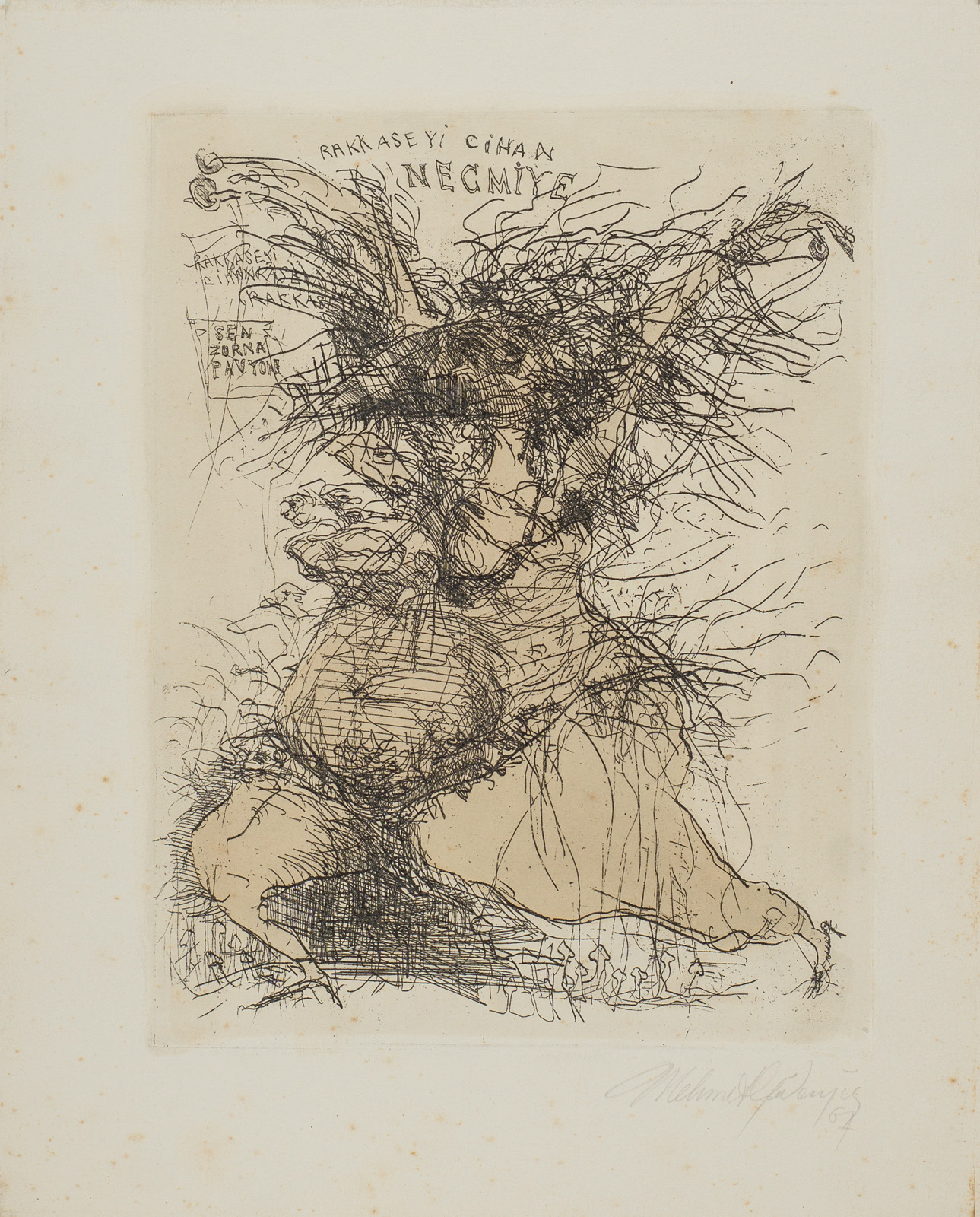

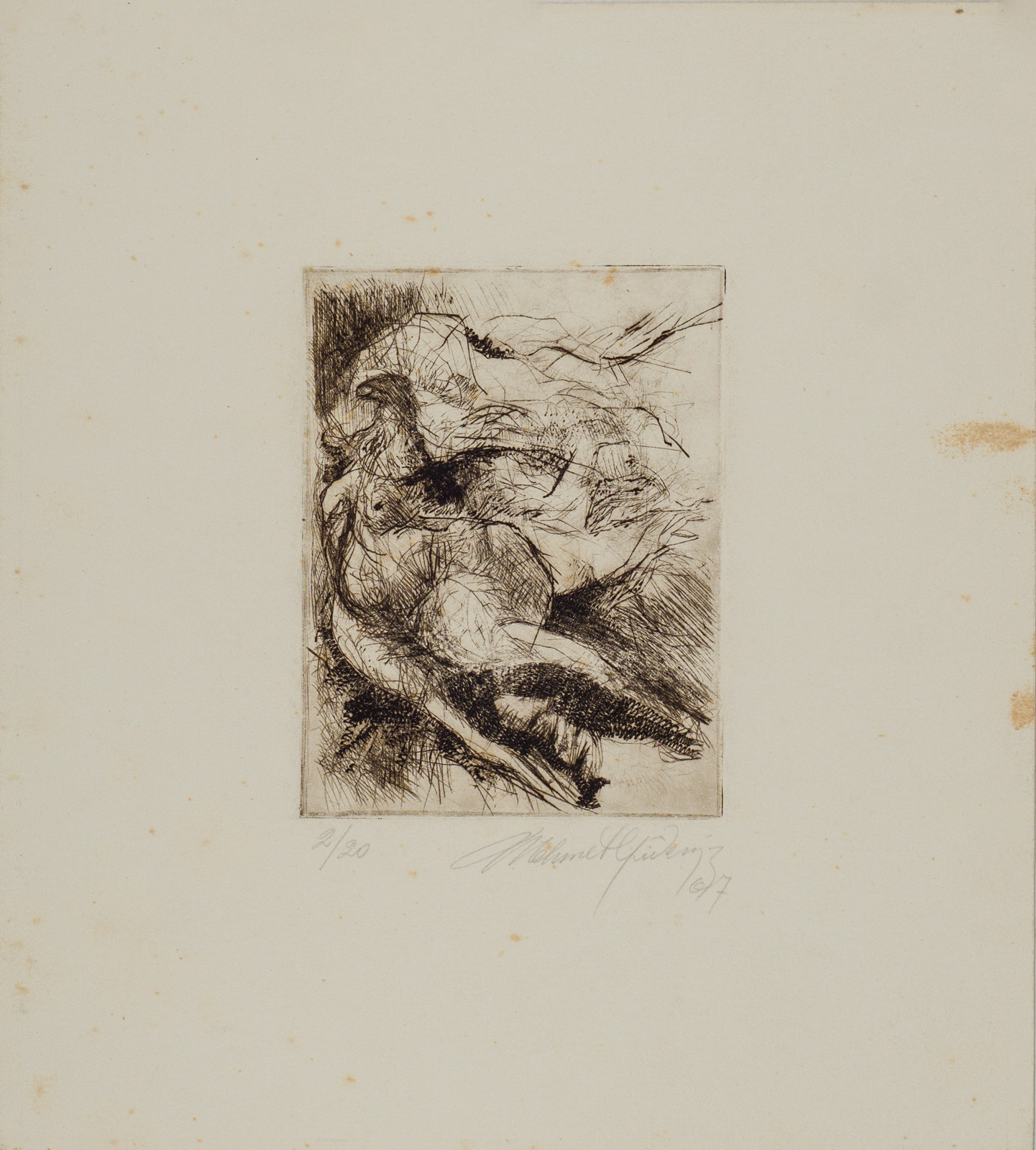

In the summer of 1965, Özer Kabaş and Mehmet Güleryüz develop an interest in engraving. They begin making small engravings with a very small press, creating self-portraits and animal-human figures. In 1967, before his military service, Mehmet Güleryüz had already conceived ideas for the figures he would later create in his drawings. During this period, Carol, who is yet to obtain a work permit in Turkey, travels abroad every three months. On her trips to Athens or Italy, she procures the art materials they needed.

The engraving workshop at the Academy is led by instructor Sabri Berkel. Although engraving is not a compulsory part of their curriculum, Utku Varlık and Mehmet Güleryüz became persistent, albeit "unwanted," regulars at the workshop. They are completely captivated by the Grand Aigle, a valuable yet unused classic large-form press found in the workshop. Sabri Berkel's cold demeanor and attempts to deter them are insufficient to drive them away.

Concurrently, they are also experimenting with lithography. Their initial aim is to introduce a new dimension to their line work and enrich their drawing language, but it quickly evolves into a profound passion. For the 1965 exhibition, Mehmet Güleryüz includes a few lithographs in addition to his drawings and paintings. He also submits his engravings to the Young Artists Biennial in Paris.

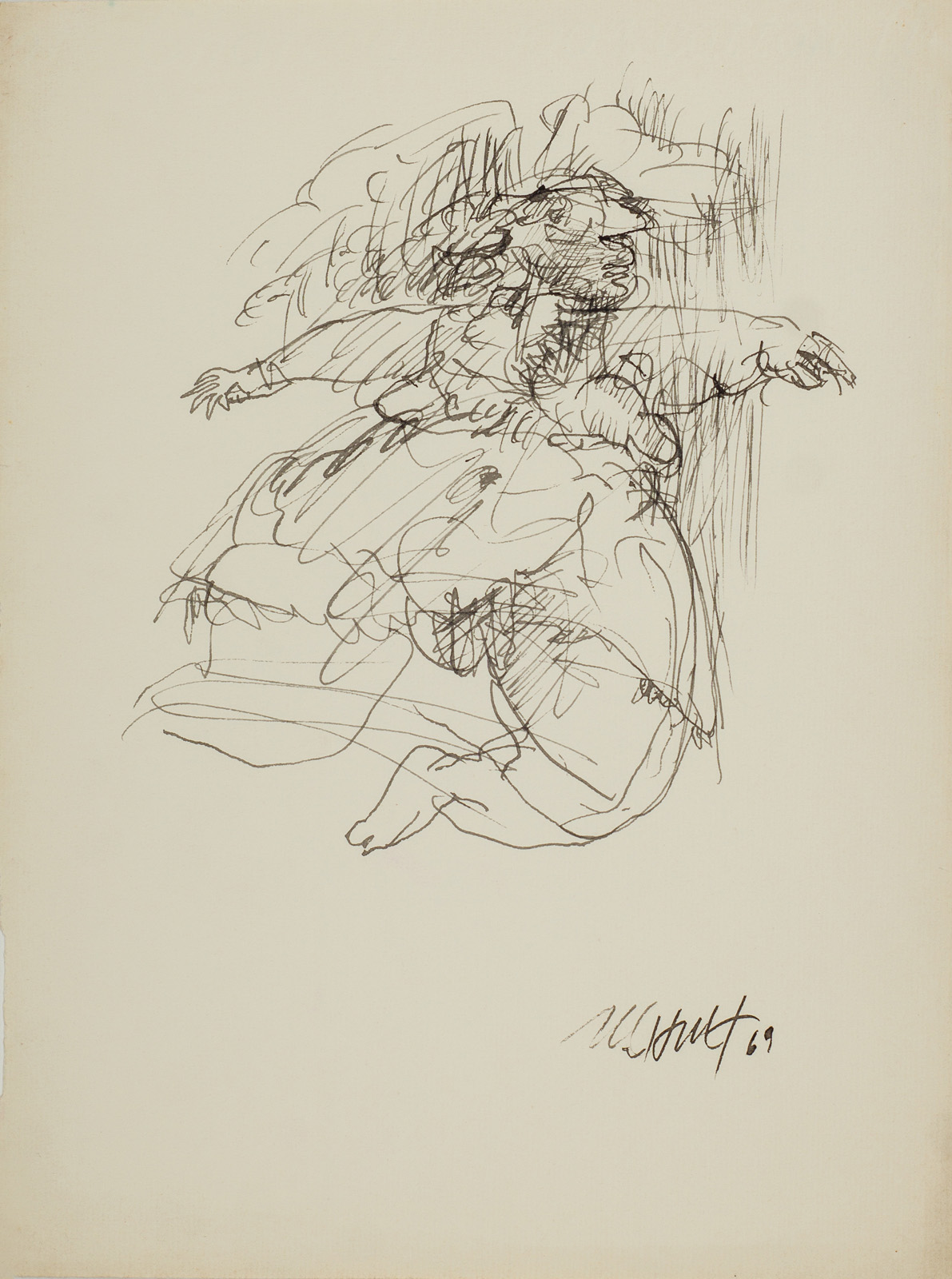

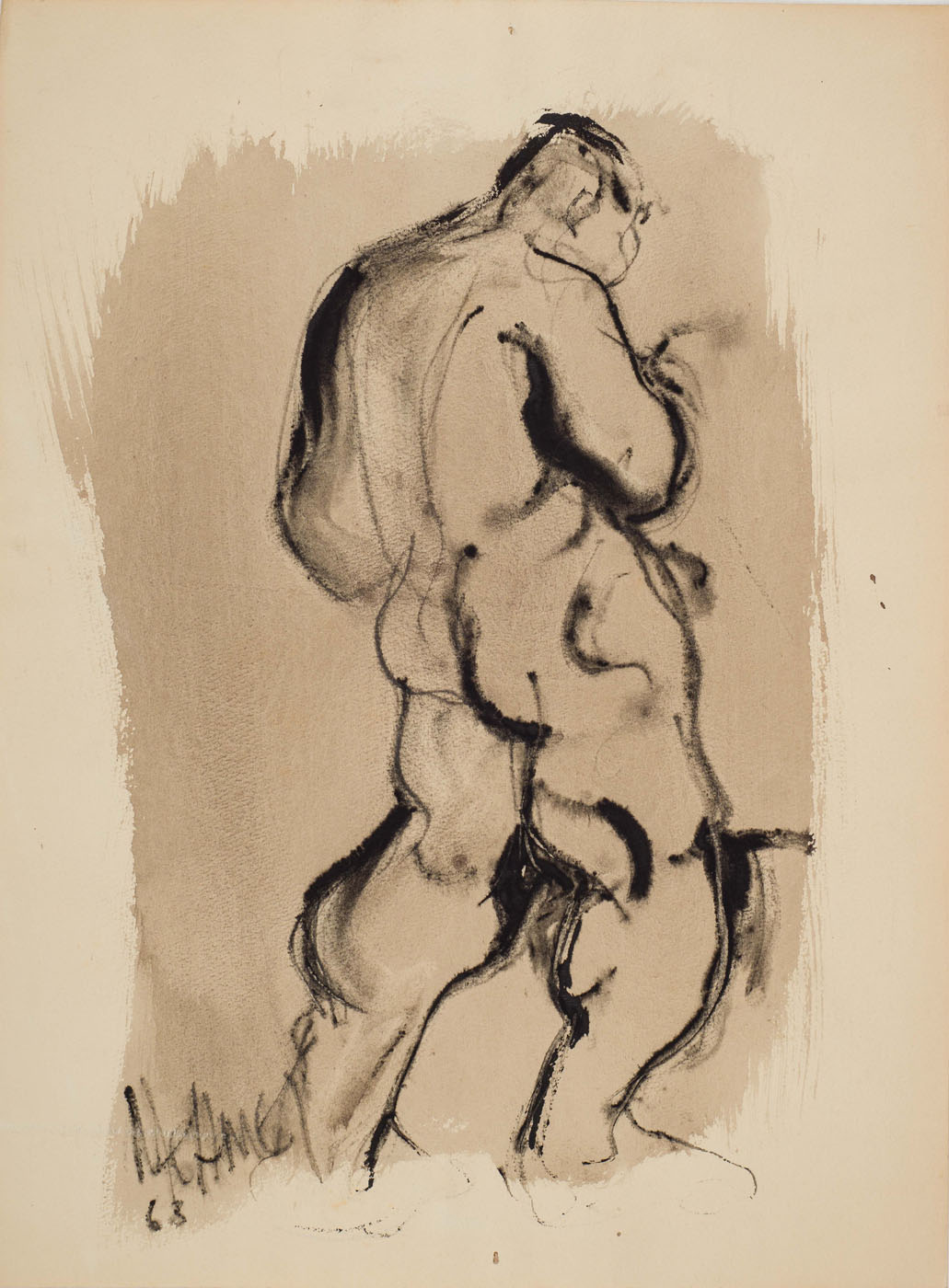

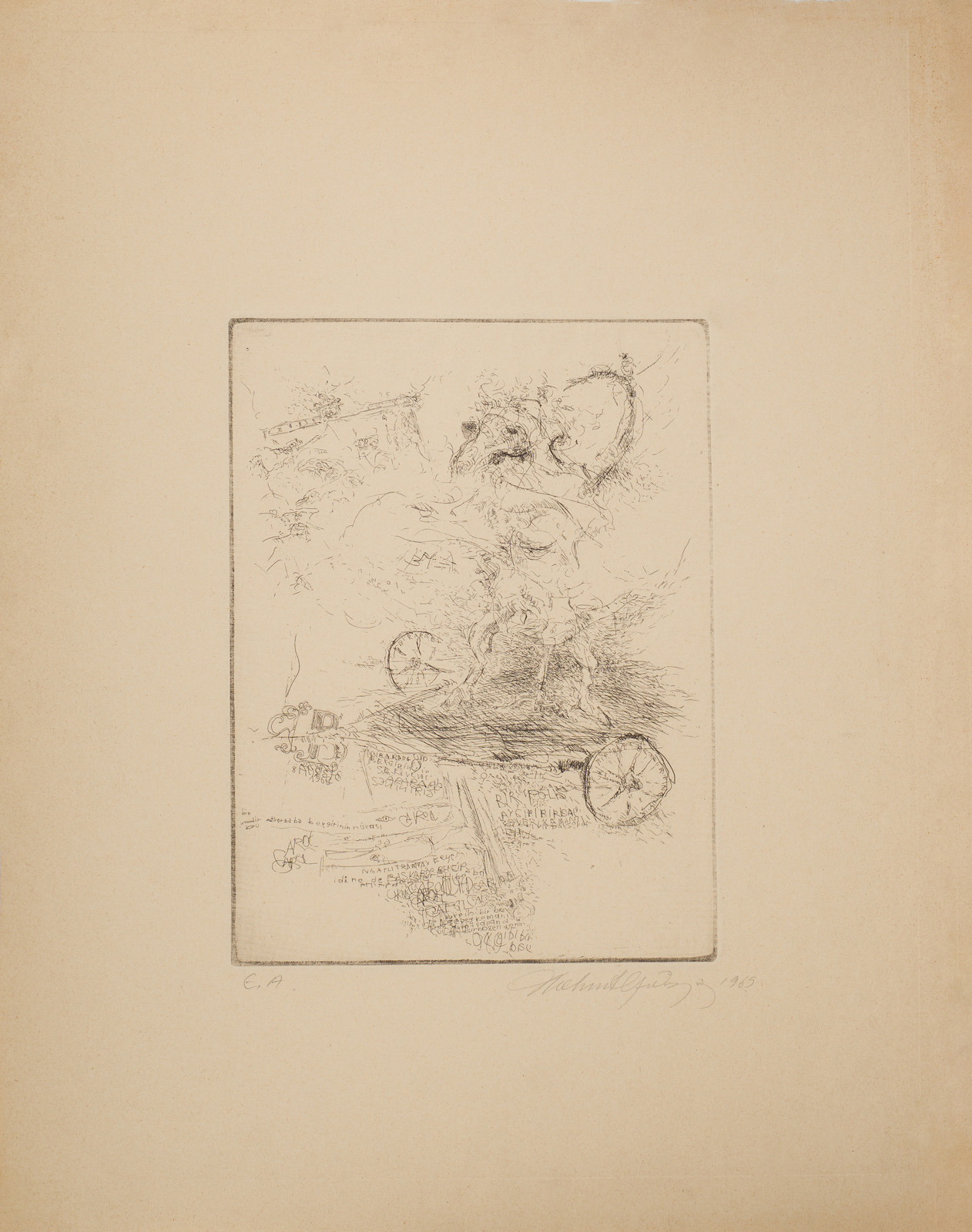

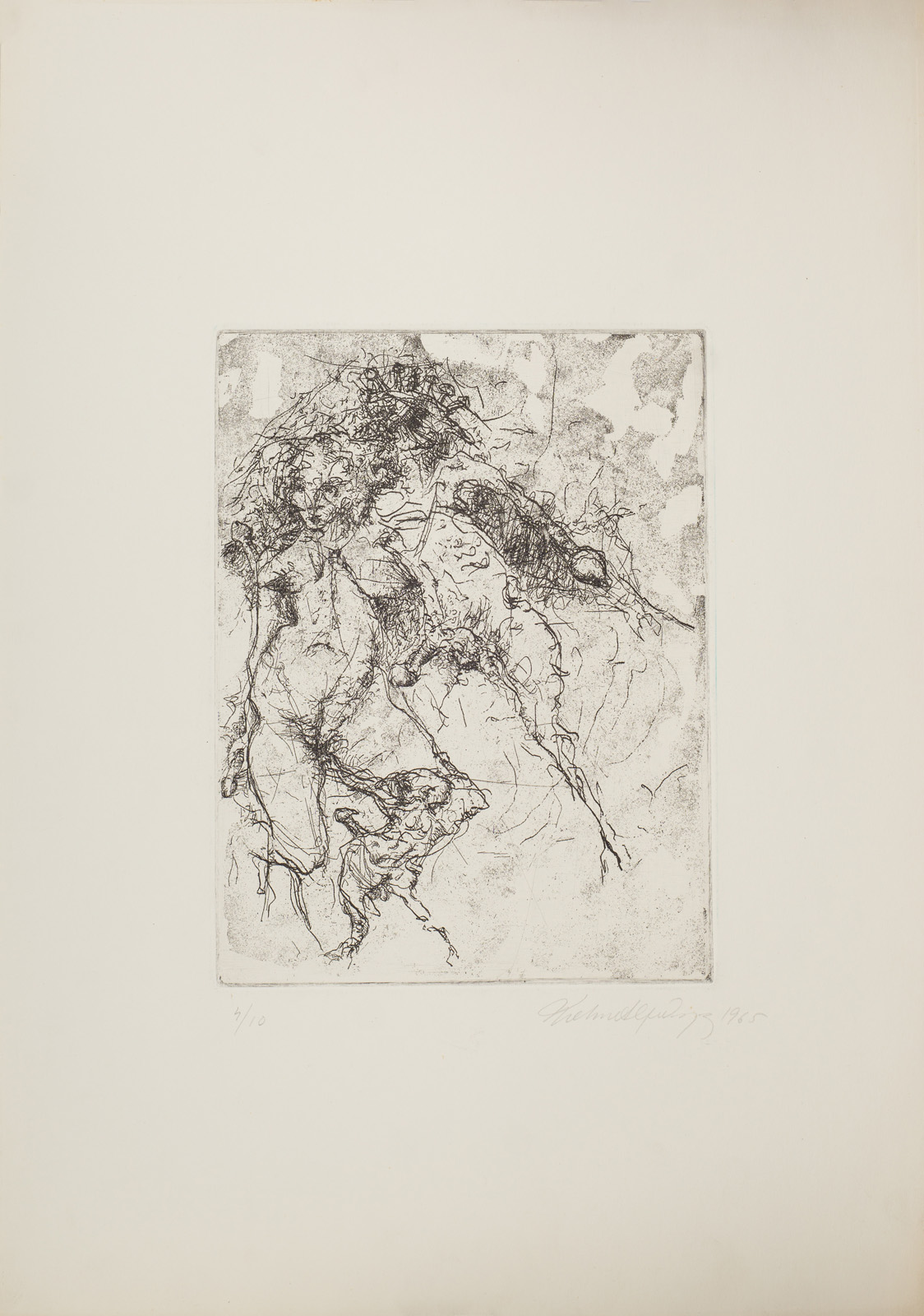

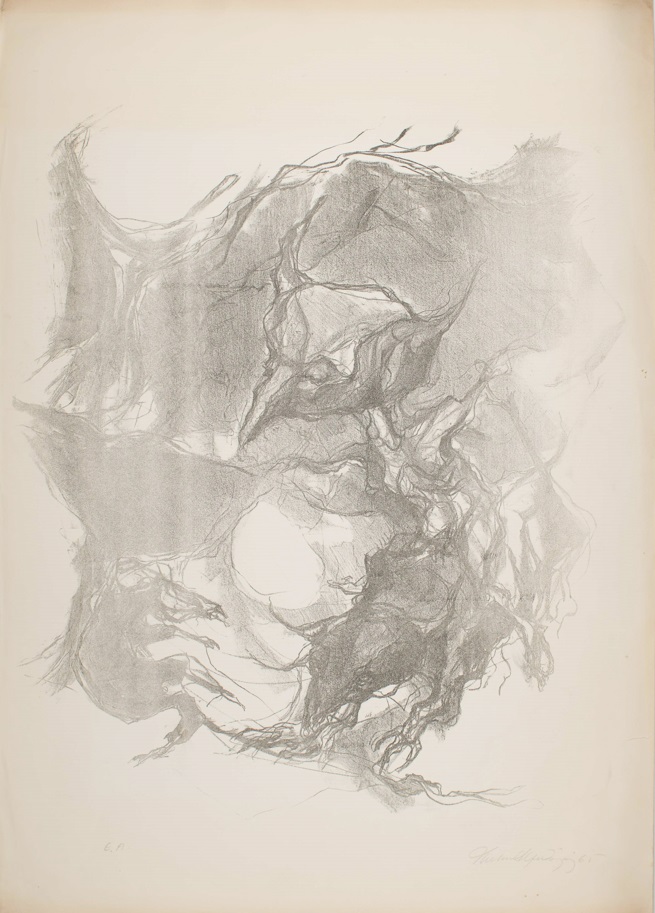

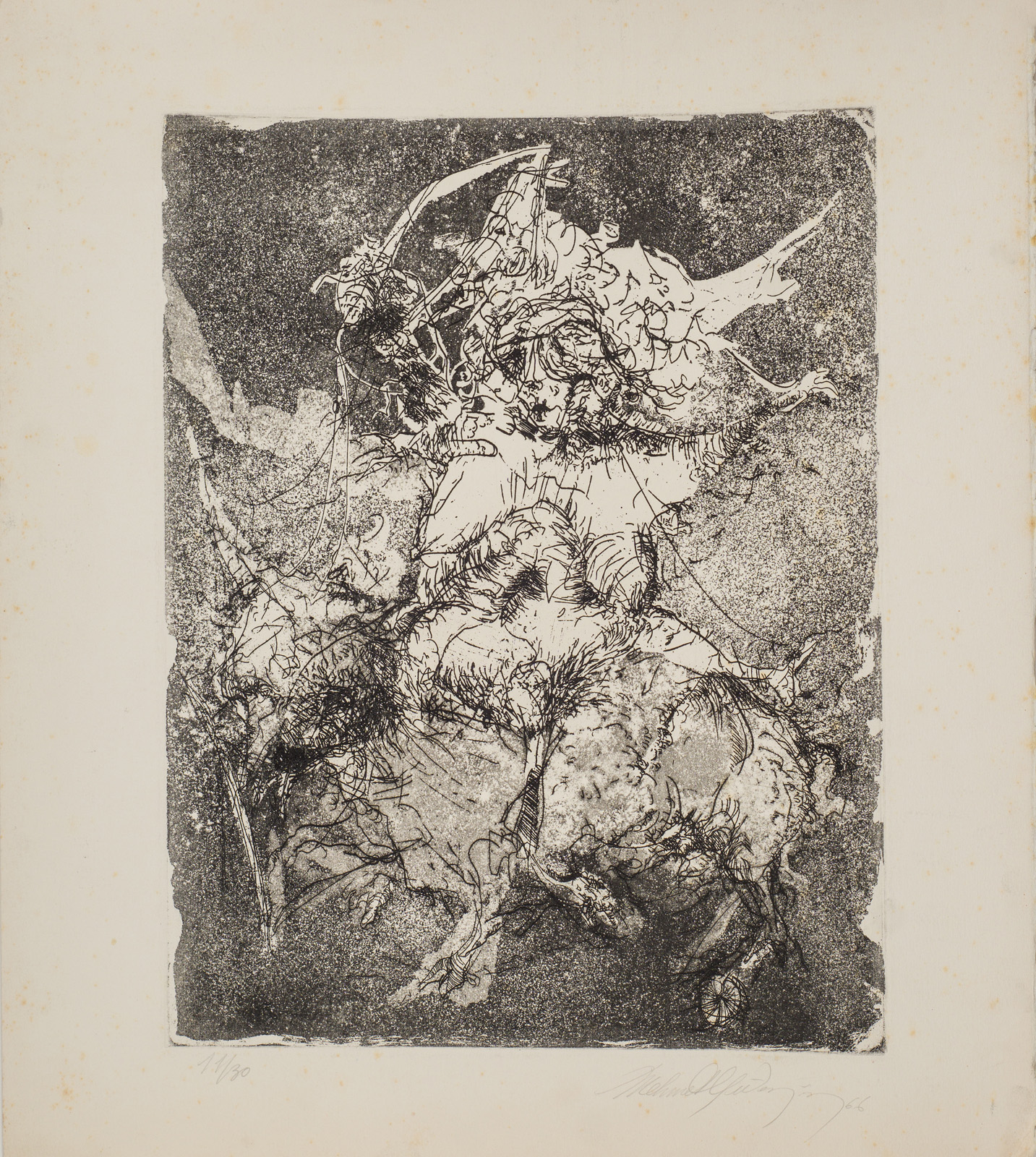

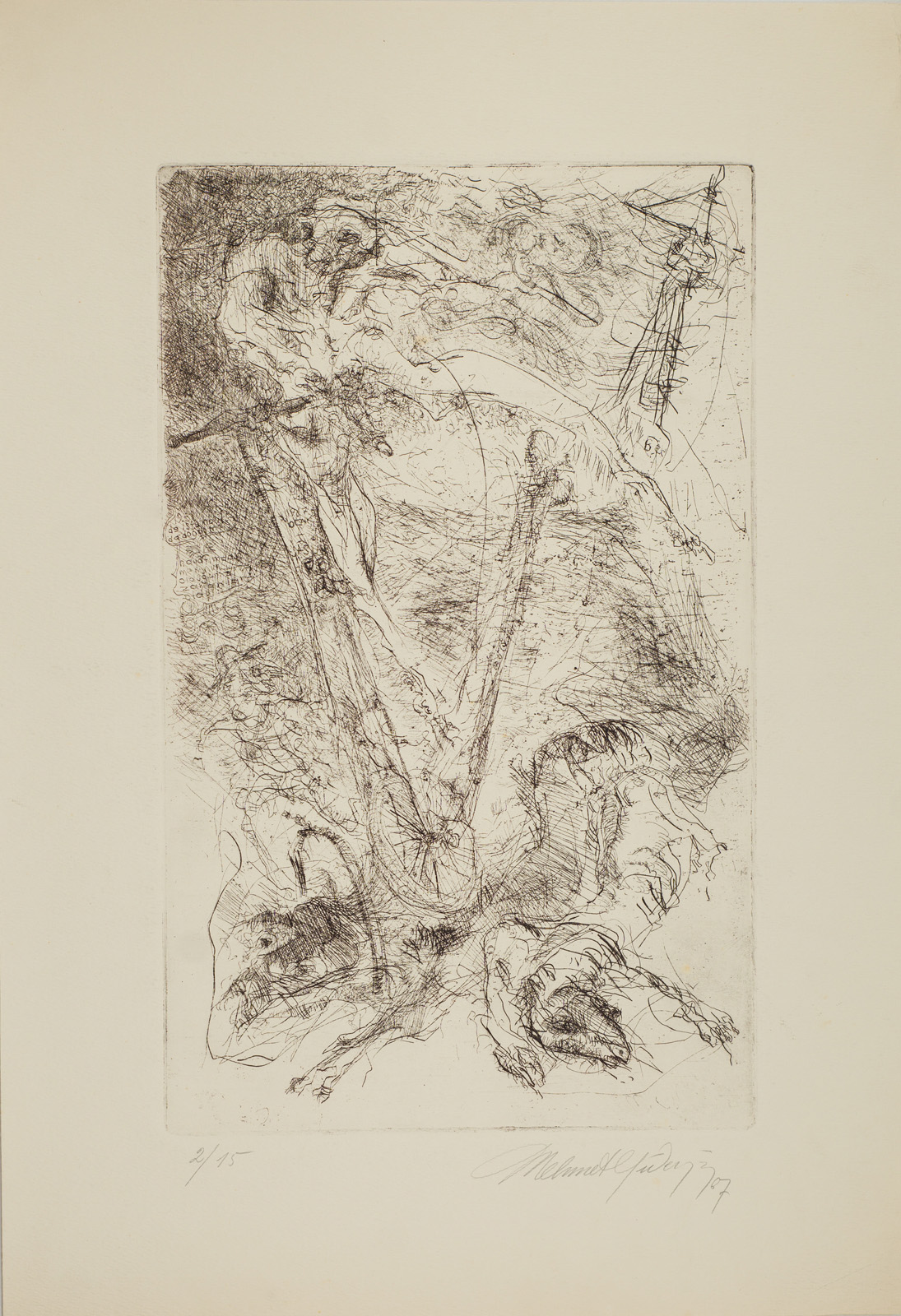

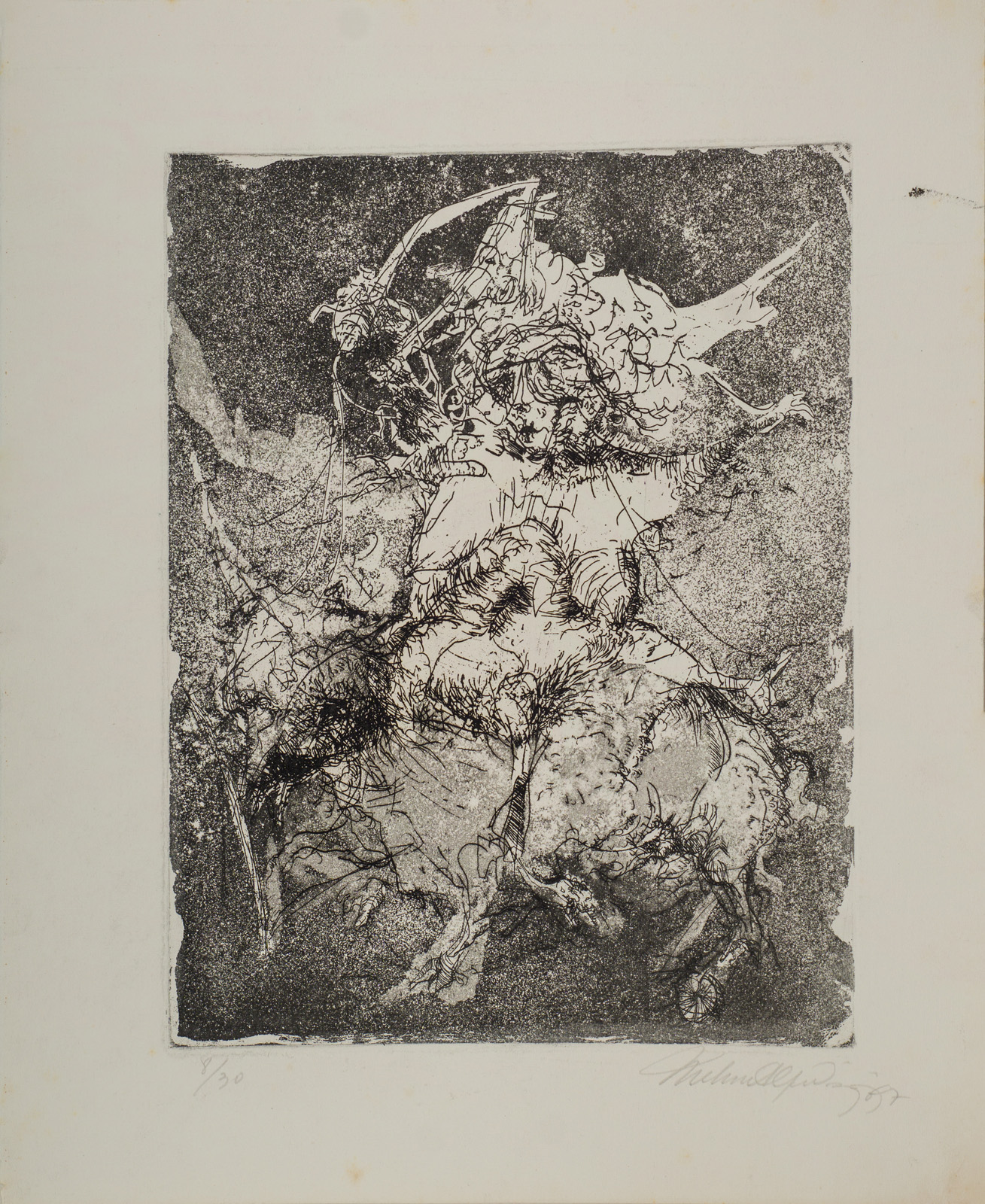

1963-65: Gravures

Wendy M. K. Shaw describes the series “Sen de Vur” (You Hit Him Too), as follows: “In subsequent years Güleryüz continued to emphasize gesture without giving up representation. He developed a mode of figural abstraction in which figures emerge from emotive lines and shades drawn quickly across the page. Despite the gestural immediacy of the drawings, the changing quality of line underscores his facility with the medium. This is readily apparent in the “You Hit Him Too” series of 1965. Here, straight, quickly drawn lines merge with meandering, ticked marks, producing tangles of cross-hatching that break off into loose threads and arbitrary coils. Layers of loose wash give body to the lines, enabling human and animal figures to emerge from the morass. Rather than giving way to flat forms, however, the contrast between the thick patches of cross-hatching and the thin washes with specks of paper showing through create a sense of deep shadow, enabling molded figures to emerge from the mess of lines. Like the games our mind plays in creating figures from the marks of steam on a shower door or cut wood or marble, these figures endure at the very limit of recognition.”

Individual and social thought processes, as well as some previous definitions, play a very important role here. Some tension areas emerge that have not yet appeared, but are sensed; for example, in the series where the painting 'Sen de Vur' I made in 1965 is included, the corner where society and I are pushed… I was feeling a great sense of anger and a need to react, to rebel. At that time, there was no such approach to painting in Turkish art, nor any signs related to sexuality. I included the depiction of sexual organs in the expansion of the figures. The figures I drew were creatures with gender.

1965 Group Exhibitions

- TMTF Peace Festival Exhibition, Istanbul, Turkey

- State Painting and Sculpture Exhibition, Istanbul, Turkey

- State Painting and Sculpture Exhibition, Ankara, Turkey

- 1965 5th Young Artists Biennale, Paris, France

1963-65: Selected Paintings

1966

Graduation

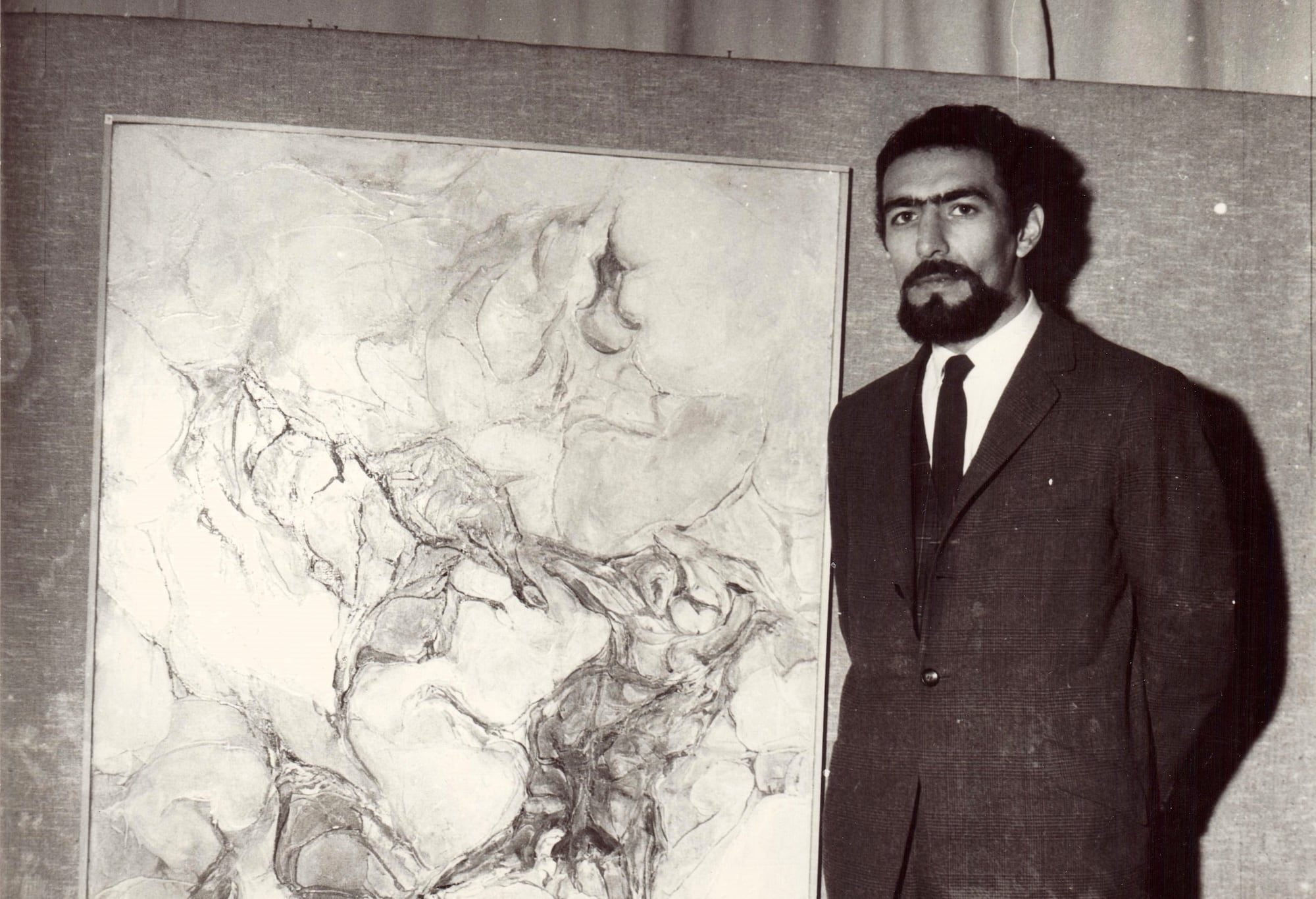

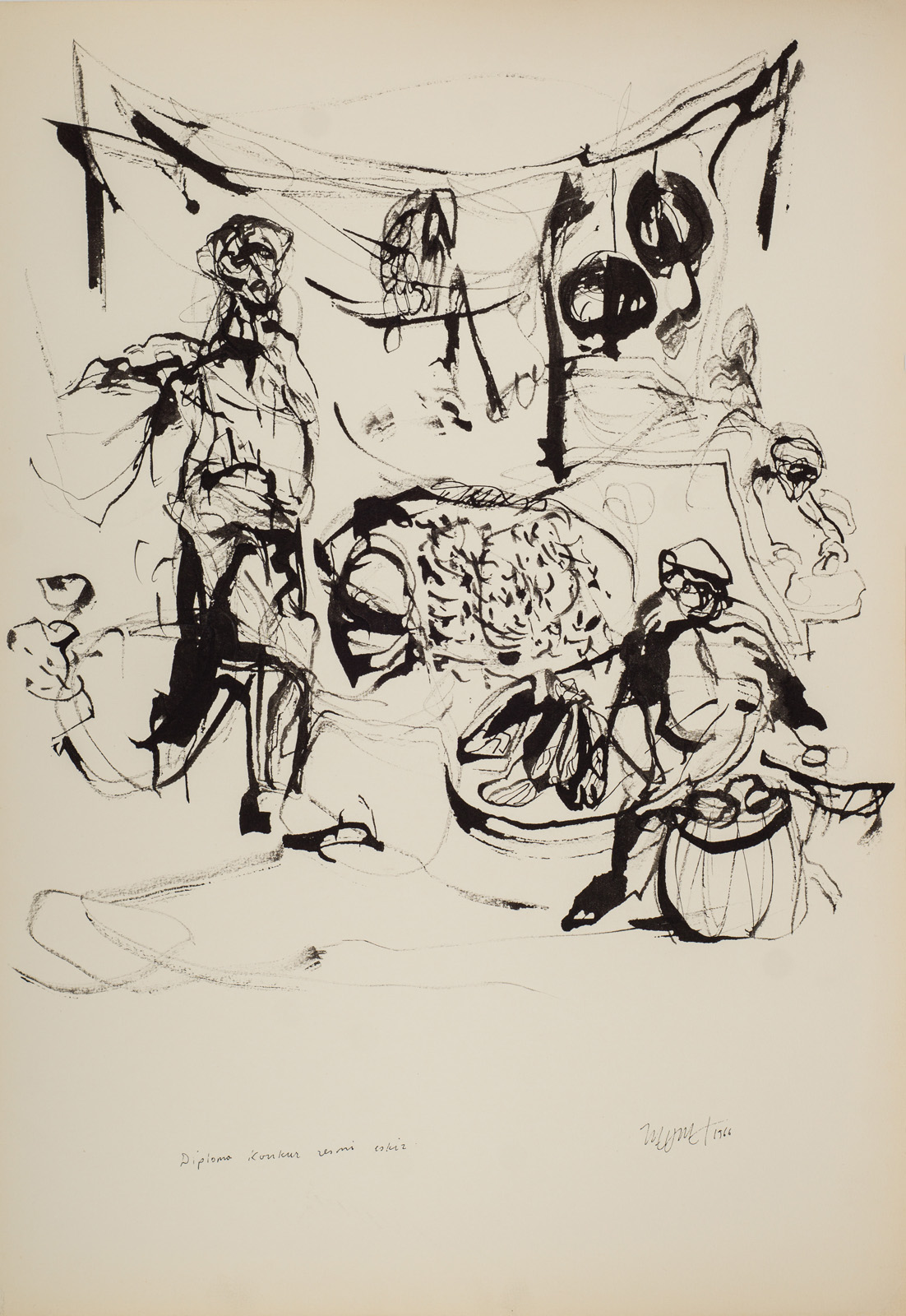

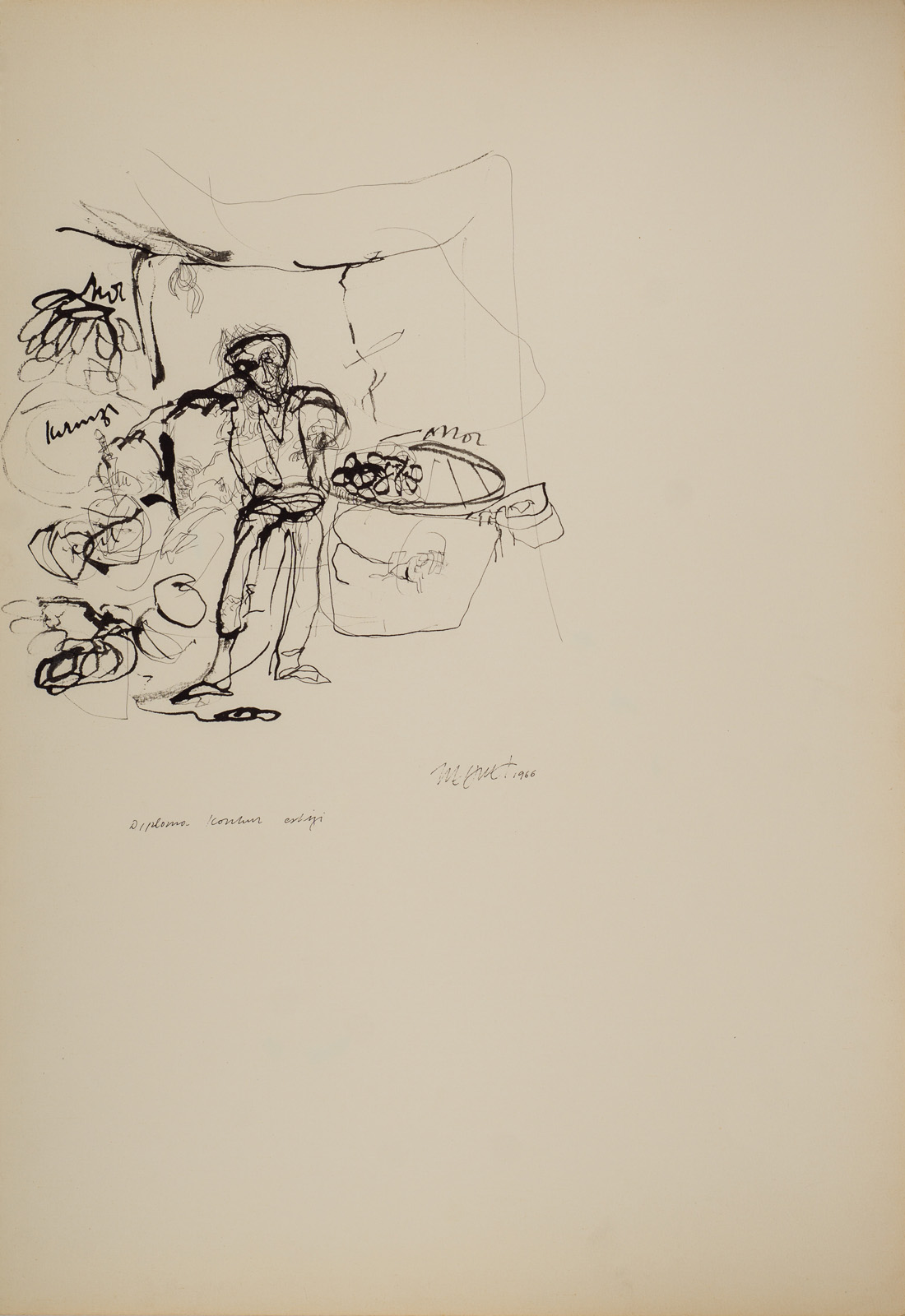

In 1966, Güleryüz participates in the Graduation Competition with his first particular figurative work, “The Fruit Seller” and graduates from the Academy winning first place.

1966 Group Exhibitions

- Contemporary Turkish Art, Ben & Abby Grey Foundation, Minneapolis, USA

- Contemporary Turkish Art, Ben & Abby Grey Foundation, Istanbul, Turkey

- Exhibition of the Contemporary Turkish Painters Association, Istanbul, Turkey

- Five Young Painters, Istanbul, Turkey

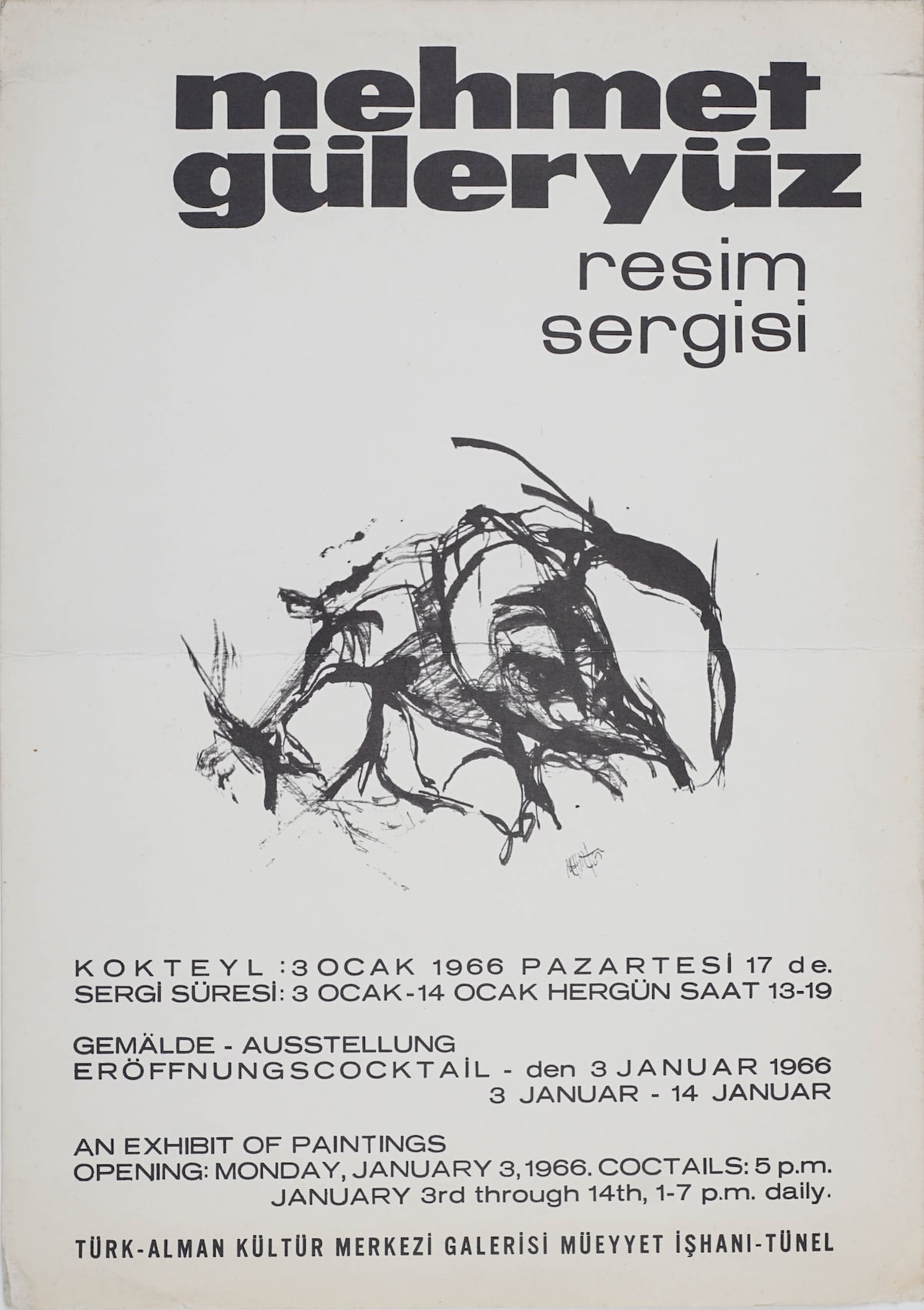

1966 Solo Exhibitions

- Turkish-German Cultural Association Gallery, Istanbul, Turkey

1966 Biennale

- 5th Teheran Biennale, Teheran, Iran

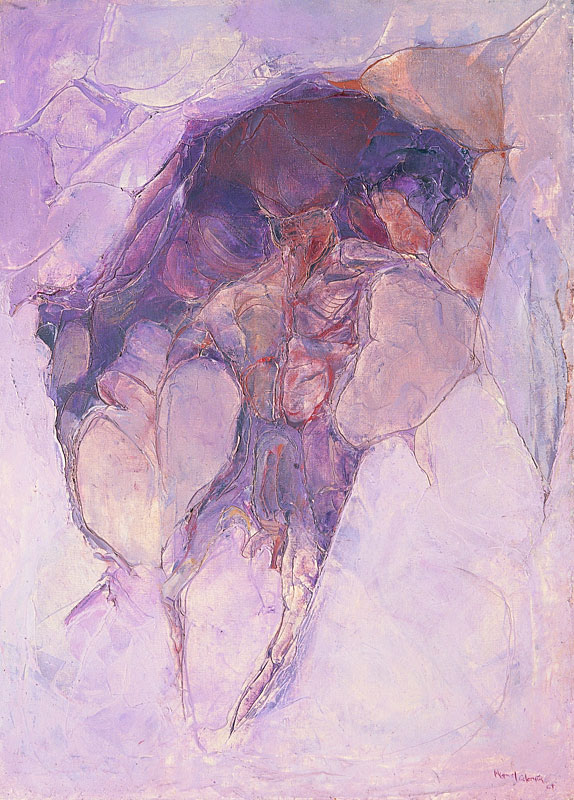

According to Nan Freeman, Güleryüz’s painting of the mid- and late 1960s, which coincided with his last years at the Academy, shows a struggle to formulate a figurative, style proper to the spirit of his generation and capable of responding directly to his individual concerns.

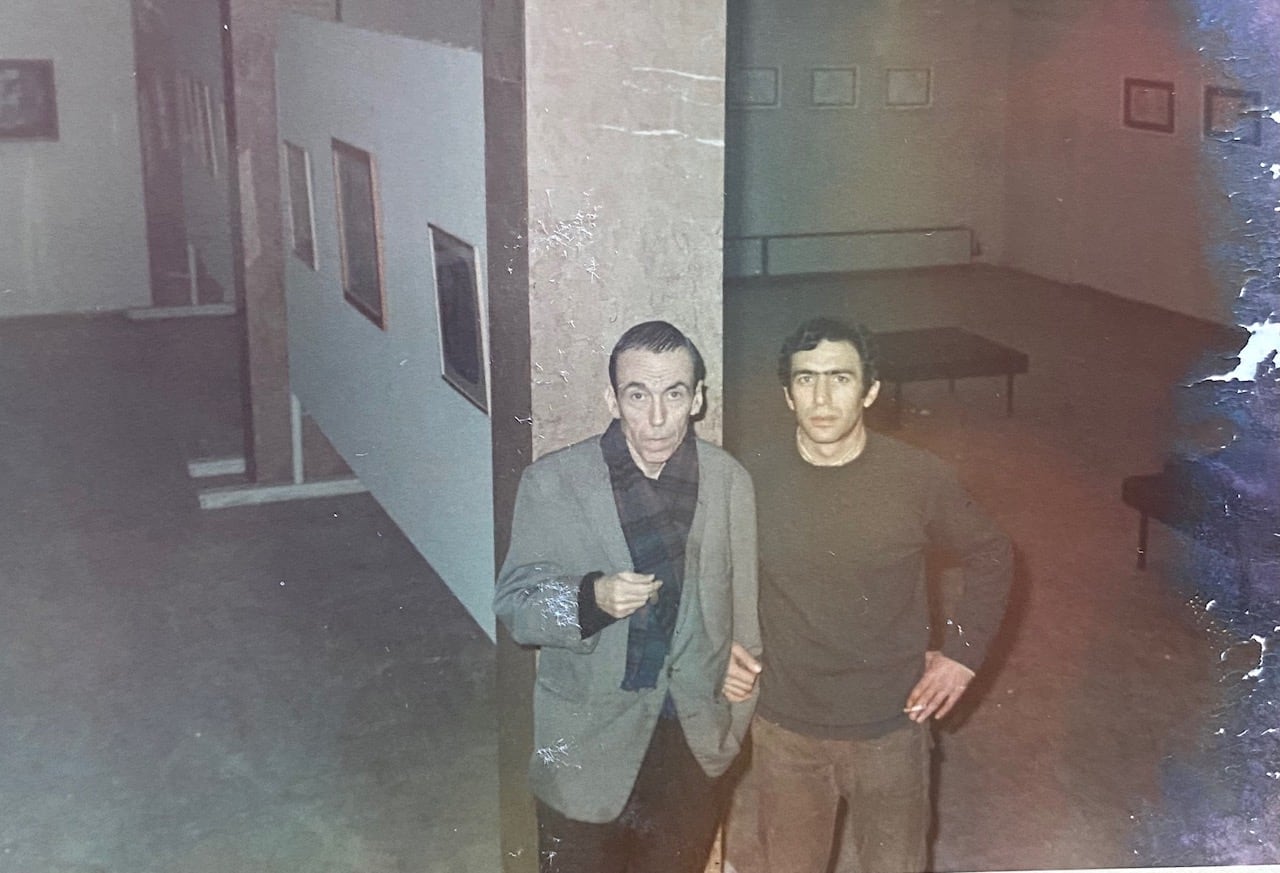

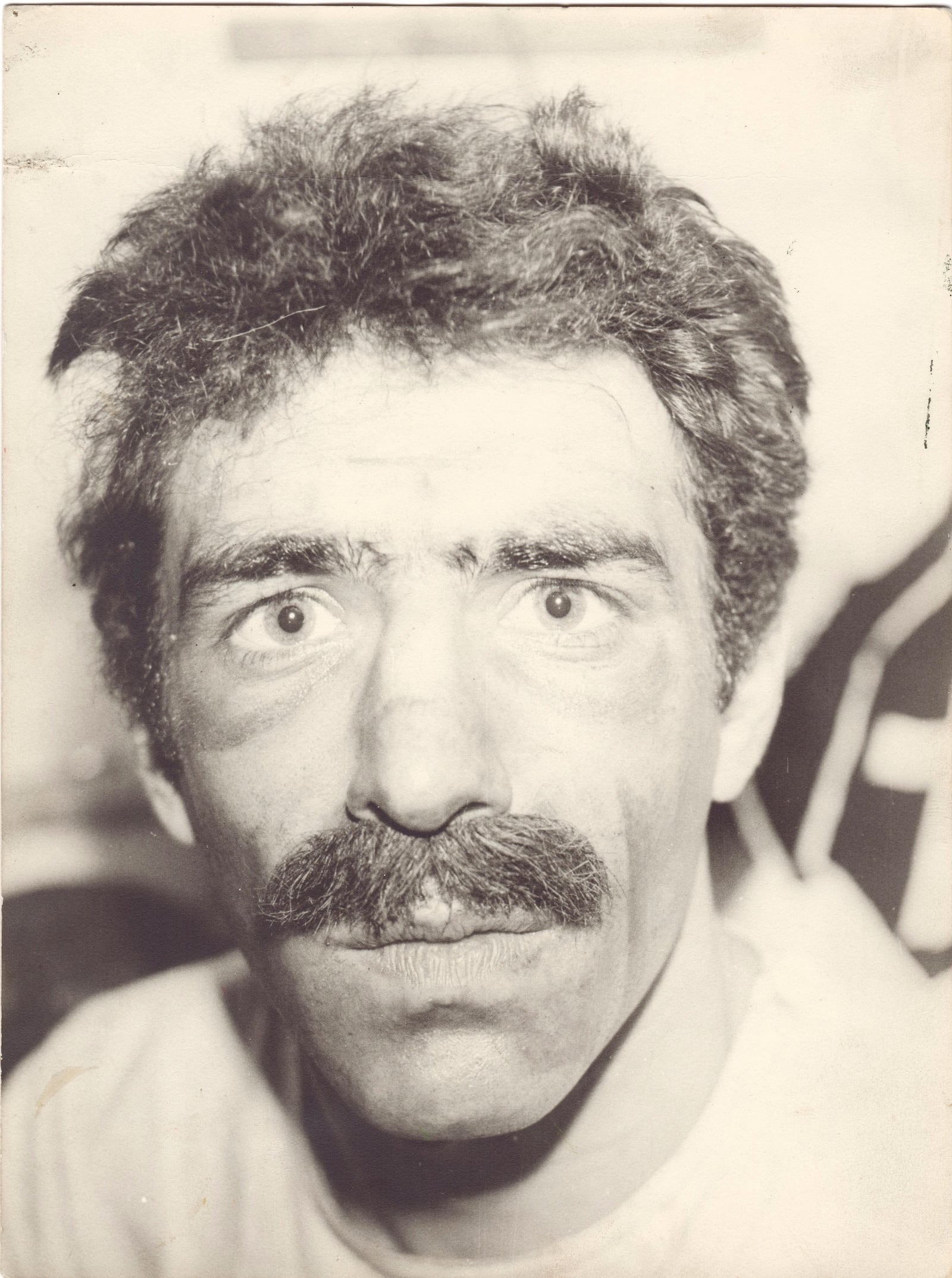

Mehmet Güleryüz, Adnan Çoker, Özdemir Altan, and Hasan Kavruk. November 29, 1966. © Estate of Mehmet Güleryüz.

1966 Turkish-German Cultural Association Exhibition

I received an exhibition offer from the Turkish-German Cultural Association. For a long time, the head of the association had been Dr. Anheger, the husband of Bedri Rahmi's sister, Mualla Eyüboğlu. They mostly exhibited professionals of that period, such as Cihat Burak, Tektaş Ağaoğlu, Nil Yalter, and Nejat Devrim. It was a time when Turkish painting was starting to stir. Being able to hold my second exhibition, especially as the first student invited there, a year before I finished the academy, was very important to me. The exhibition attracted a lot of attention. Two of the paintings exhibited there, designs from the "Caucasian Chalk Circle" series and 1965 oil paintings, were acquired by the Central Bank Collection in the 90s.

1966: Drawings & Gravures

1967-1969

Military Service

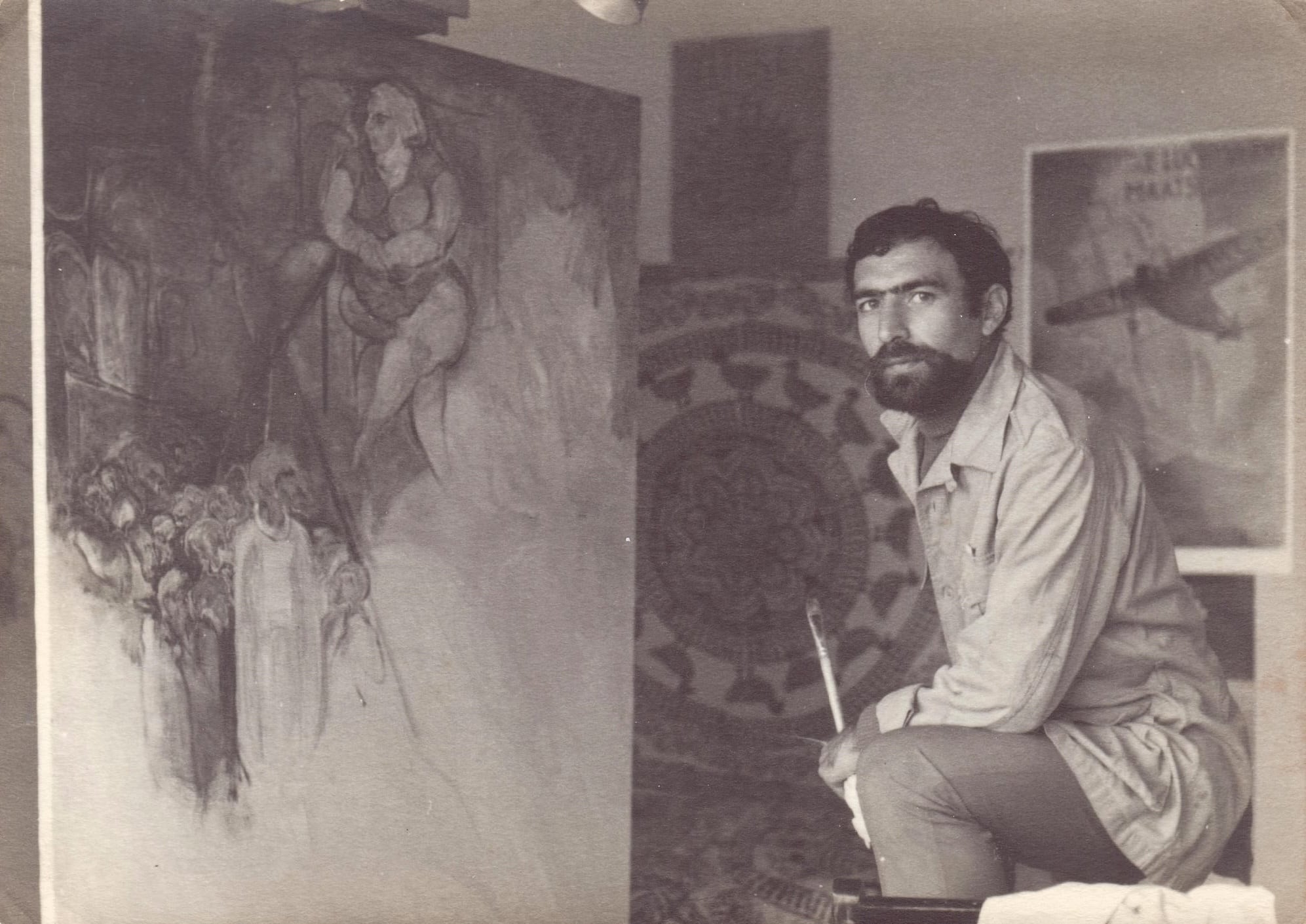

In October of 1967, Güleryüz thought he wouldn't be able to paint during his military service, fearing those two years would be taken from him and he'd experience a void. Because of this, he truly threw himself into painting, approaching his work at full speed and freeing himself in terms of expression.

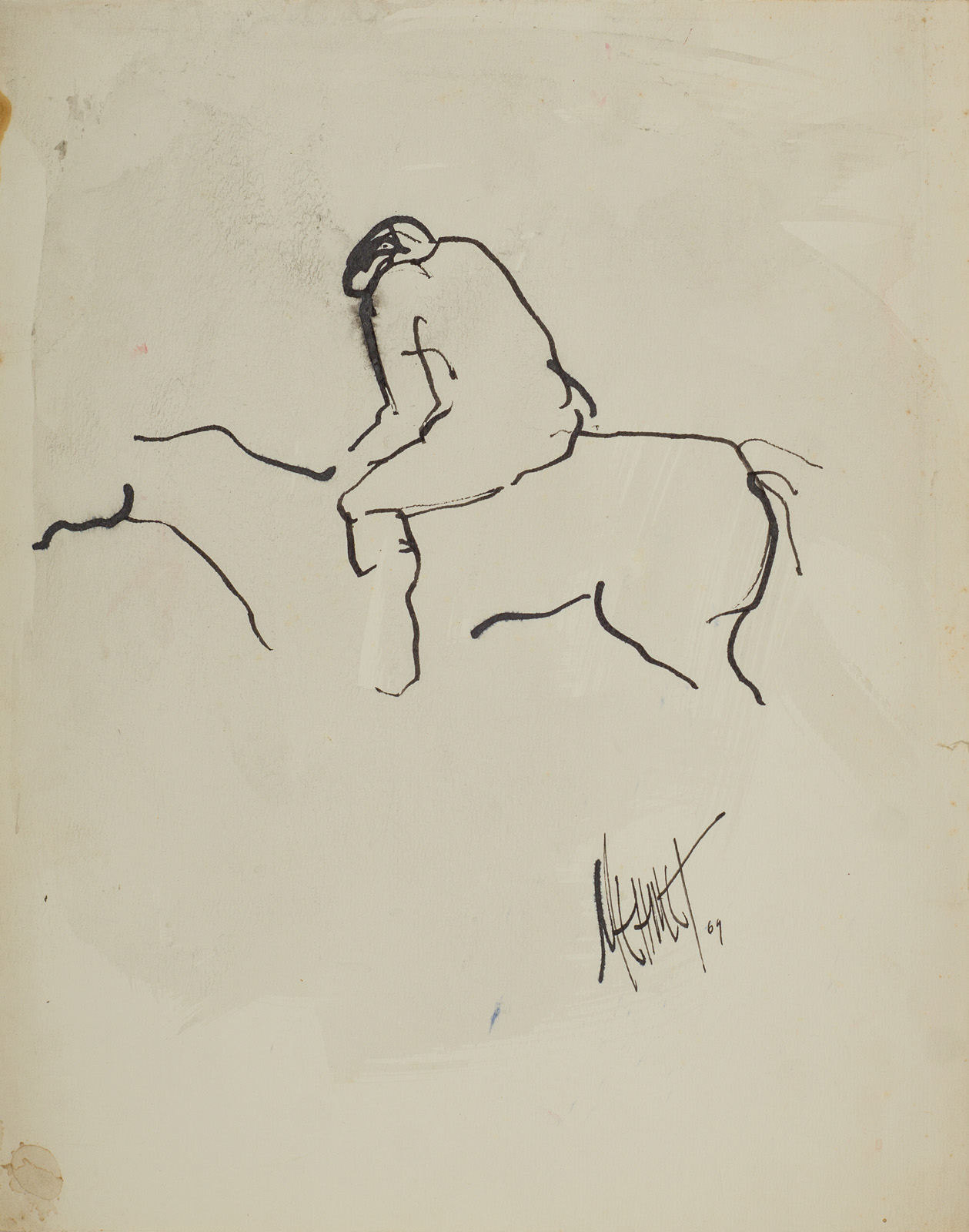

During that period, 'Through the Mirror,' 'Family,' and the first work from the 'Woman' series, 'Lamb and the Nude,' were created. These were fast, energetic paintings that dealt with current issues, starting from a fantastical realm and touching on the surreal. In 1965, Güleryüz was searching for a merging of human/animal form and the effect of stripped-away skin. At that time, the view was that dealing with current issues in painting was a very commonplace approach. However, on the contrary, he wanted to elevate and clarify his inner constructs, his ironic approach, and the critique he directed towards the social structure.

Through the Mirror became the first painting of that period. On the right side of the painting, there is a mirrored cabinet; the portraits visible in the mirror are conversing with the old prostitute standing in front of it; on the left, there is the atmosphere of the Kuledibi antique market and a naked man with a green cap who is engaged in a relationship with a cow.

The Lamb and the Nude is the first of the paintings addressing sexual pressure and the oppression of women. At that time, sexuality, the body, and skin had become my primary concerns, and during my theater studies, I had adopted the words of my playwriting instructor: 'Talk about what interests you the most!'

“In the mid-late 1960s Güleryüz began the first of his paintings that function as tales; narrative scenes with fantastic as well as realistic imagery, metaphorical content and multiple meanings, some of which are intended as critique of the social order of which he is a part. He gives these scenes settings which refer to a real or a fanciful local context.”

1967-69: Paintings

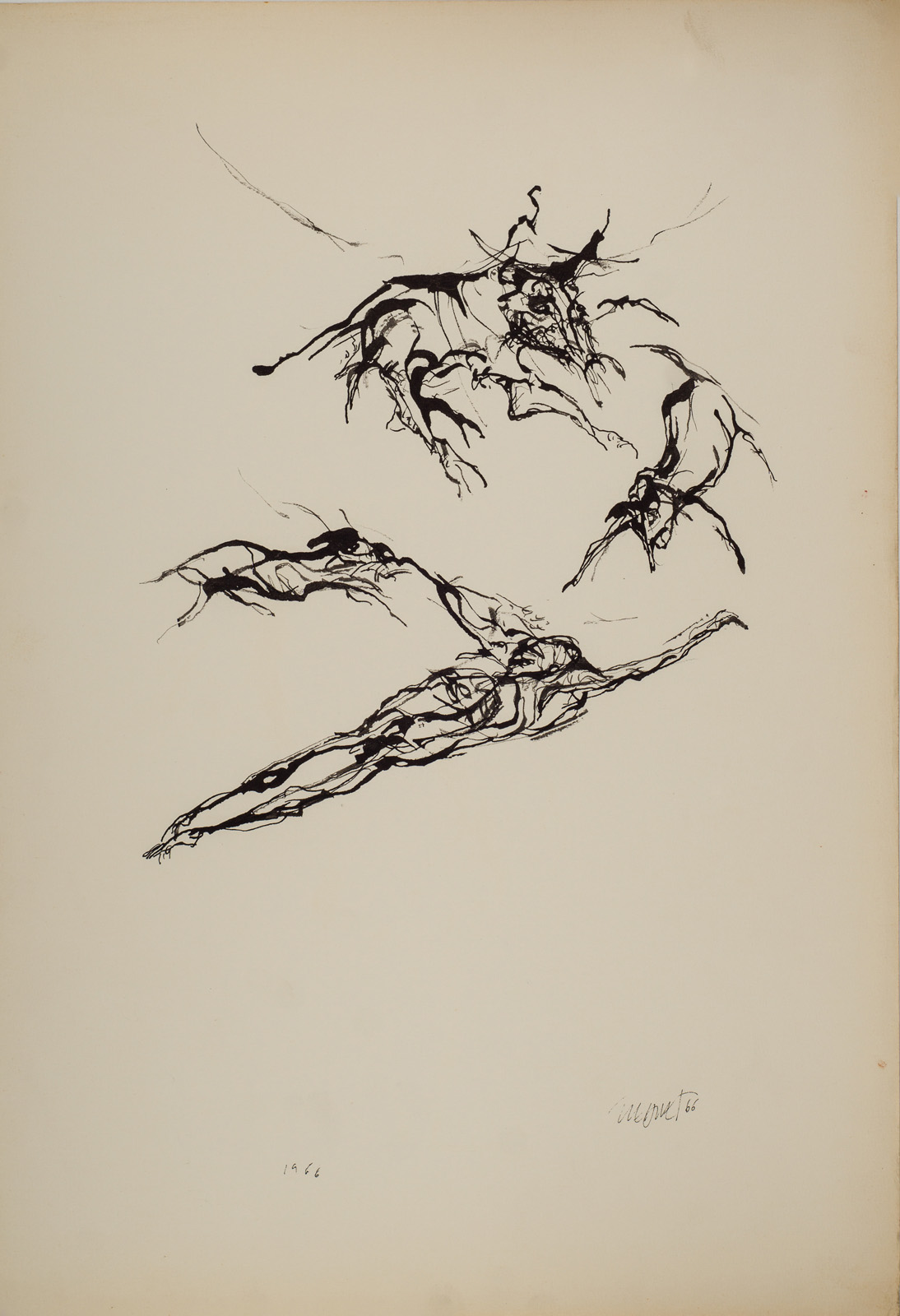

The engravings Özer Kabaş and Mehmet Güleryüz print in 1966-67, and the drawings he makes in Bursa, attract a lot of attention. The connection between the engravings and the drawings, the use of drawing as a separate expressive language, the relationship between the drawings, and the emergence of the theme of sexuality are all notable. The sensuous atmosphere and its energy, reflected in the language of painting, are quite progressive and daring approaches for that time. The most important aspect of this exhibition for Güleryüz is overcoming the hiatus during his military service and being able to create art.

1967-69: Engravings & Drawings

1968

Taksim Art Gallery, Istanbul exhibition

In one of the two halls were my paintings, and in the other were those of Aktedron Fikret — that is, Fikret Andoğlu. That exhibition was enjoyable for both of us; we got to know each other better. At one point, I wanted to make a short film about him. In the film, Aktedron would take on the role of the muse: the muse visits a painter, but the painter isn’t home. The next morning, the muse crosses that painter off the list — only to realize there are no names left in the notebook. So, the muse starts searching for an artist. I told him about it — he chuckled and said, “We’ll do it, we’ll do it!”

The unique sense I felt in the delicate light surrounding him made me think, “If there is such a thing as a muse, it must be someone like this.” Through his sense of art and intuition, he had grasped elusive sources that are difficult to access. His connoisseurship had developed along this path and had affirmed itself through his exceptional instincts. Aktedron is one of the names I would count among my mentors. Teachers like him often don’t even realize what they’ve taught.

1970

Taksim Art Gallery, Istanbul exhibition

There were about seventeen oil paintings. One of them is now in the Painting and Sculpture Museum Collection. Sabri Berkel had the authority to acquire paintings for the museum, and he was selecting works from the exhibition. The selected painting featured a male figure with a knife, sitting as if riding on a woman with a sheep’s head — a composition symbolizing male dominance. The title: The Lamb and the Nude.

It was the winter of 1970. On a gloomy, rainy morning, I boarded the trolley bus in Bebek to go to the exam. The ticket seller sat on the right, just inside the back door, with a foldable counter in front of him, where he would sell tickets to those getting on. My eyes were drawn to the ticket seller. A massive, heavy figure, with a gray-yellow face; slightly shaved, without a mustache. He wore a leather vest, a gray coat over it, a money pouch around his neck, a wooden ticket box on his knees, rubber boots worn over felt socks, and a hat with a metallic number written on it—Five hundred, etc. He looked like a monument of sorrow! I froze. I watched him all the way to Fındıklı. I got off the trolley bus while still looking at him. 'Oh God, I hope they give me a suitable subject so I could paint this man!' I thought to myself. The subject was given: 'A Scene from Life.' If I put to paper everything I was thinking, I wouldn't be able to make the painting, so I roughly sketched out the outline and submitted the sketch. Upon receiving approval, I completed the ticket seller in one day. I didn’t pay attention to the empty space behind him. Later, I added my own childhood memories of the comings and goings between my mother and father behind the ticket seller. In the empty yellow atmosphere, there’s an elderly woman, with a child in silhouette leaning against her. The painting received full marks from the jury."

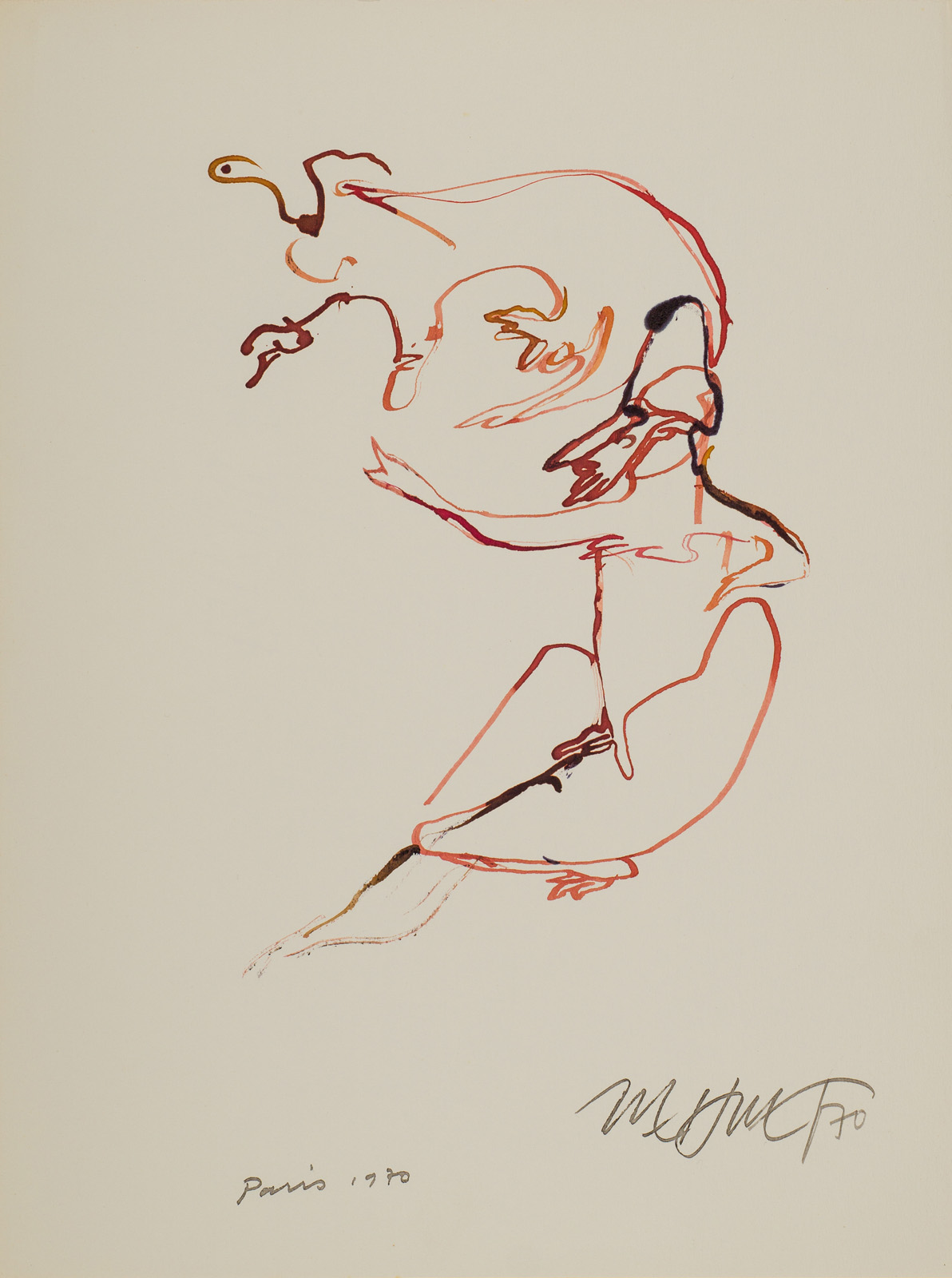

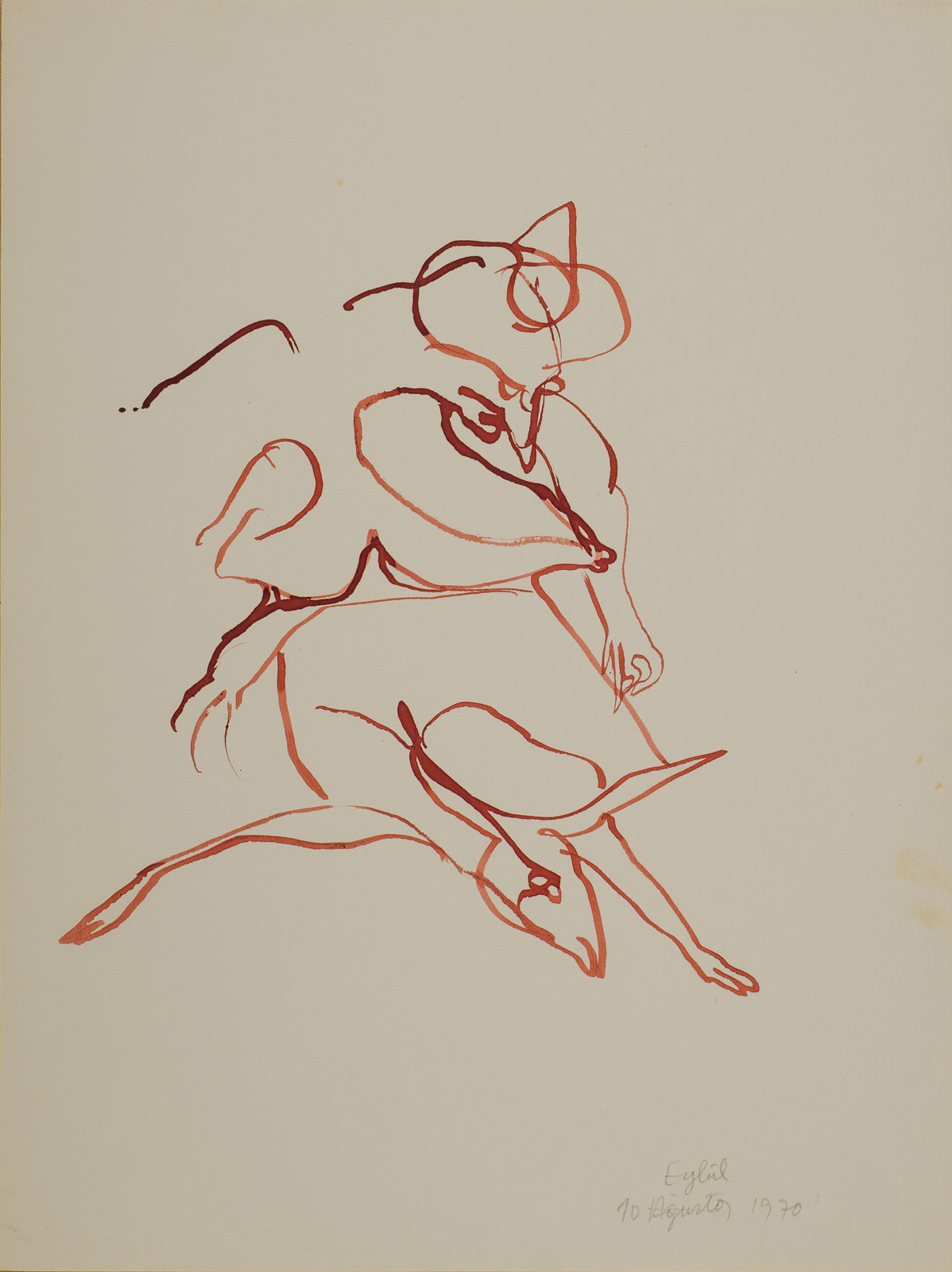

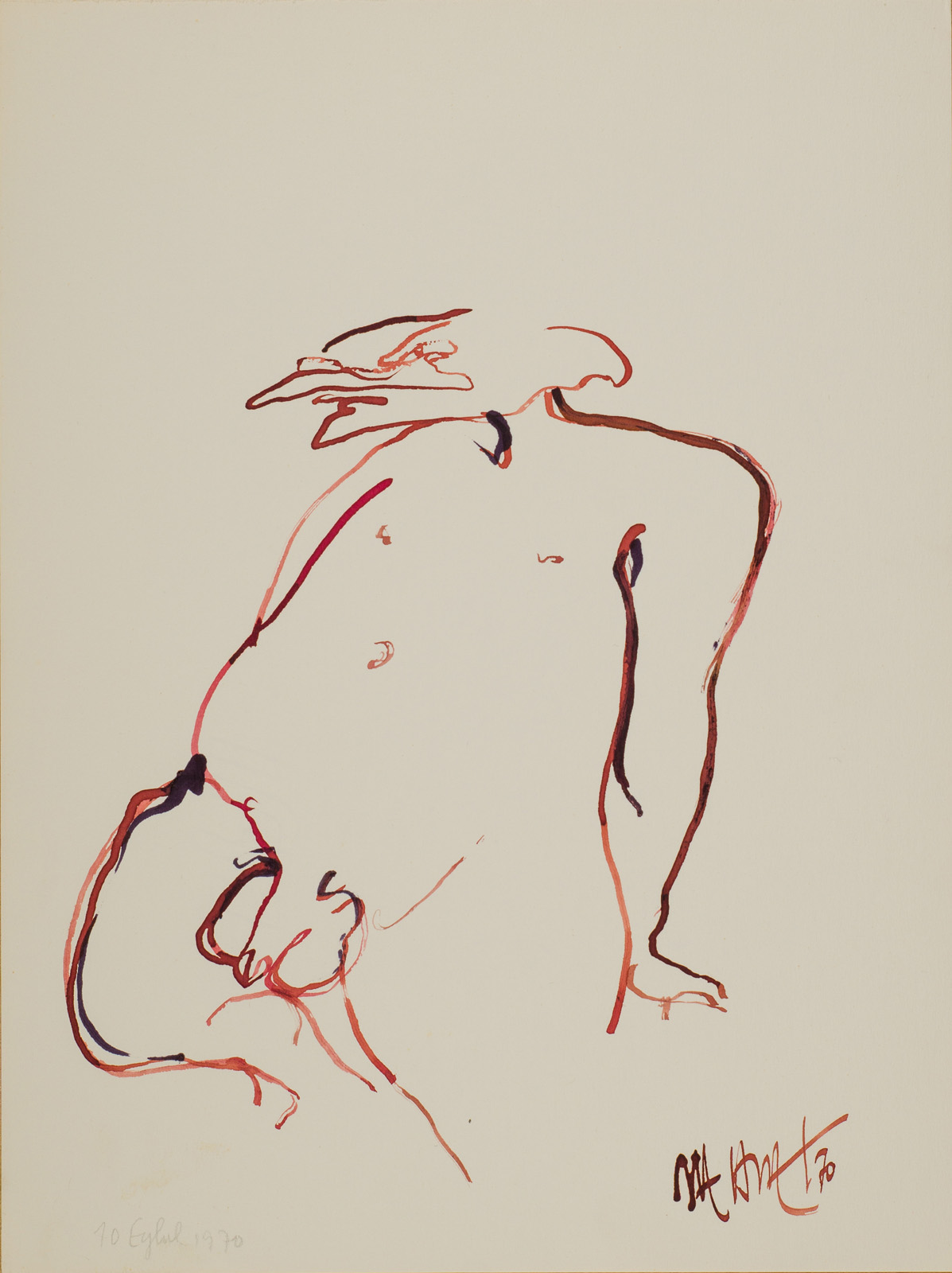

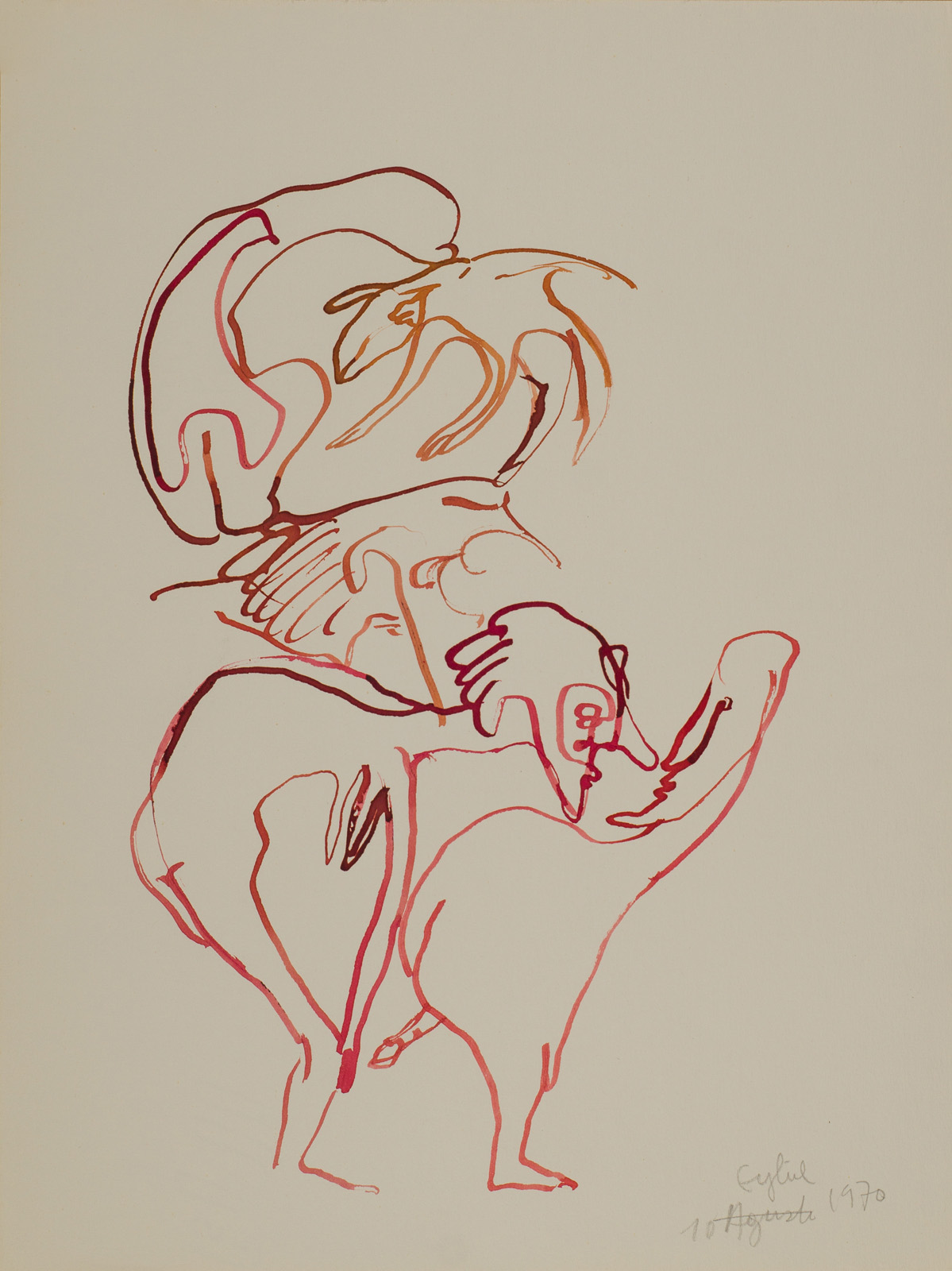

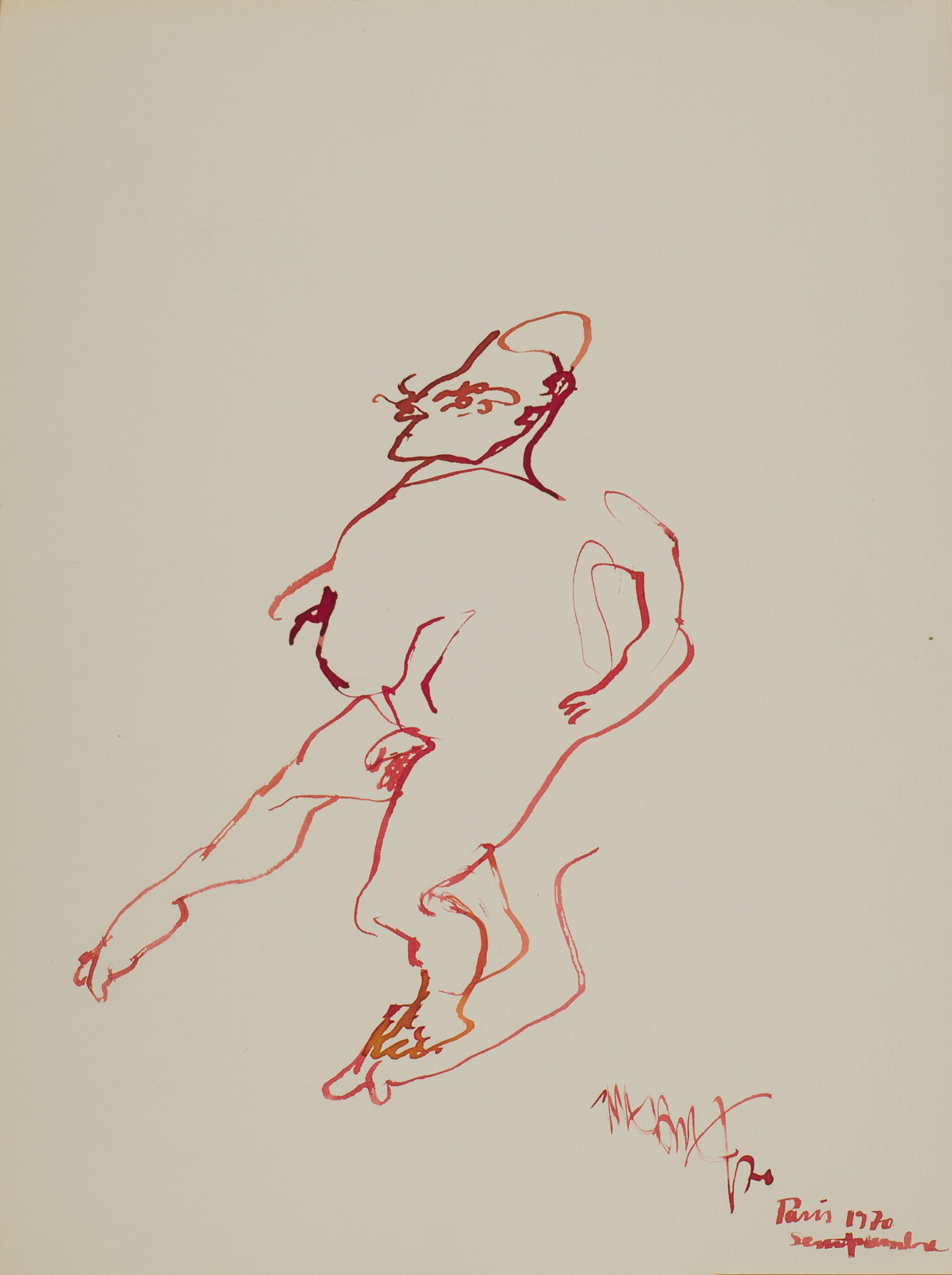

1970: Drawings

.jpg)